Labels: Equipoise, Patient things, Real World Math, Trinity House

Houghton hypothesized that if a more moisture-absorbing chemical were introduced to the fog, water molecules would attach to the new compound, vapor pressure would drop, and the fog would dissipate. He scattered calcium chloride, an inexpensive compound with such properties, onto a dense layer of artificial fog and watched as the fog vanished. Field trials in which a calcium chloride solution was sprayed onto natural fog yielded similar results, but the technique wasn’t practical for clearing fog from sizable patches of land. To do that, and to counteract the way the wind pushed new fog in, Houghton suspended a 100- foot-long pipeline with downward-facing spray nozzles from 30 feet in the air. When set up perpendicular to wind direction, the apparatus shot a misty curtain of calcium chloride toward the ground, dispersing any fog rolling through. Spraying 2.5 gallons of the compound per second, Houghton’s machine took only three minutes to turn an area with visibility of less than 500 feet into one where “buildings more than a quarter-mile away were visible,” according to one report.In short, the MIT fog control project WORKED, and it worked by the same methods used in cloud-seeding. The article doesn't say why the effort was abandoned. The experimental system required too much salt, but a serious engineering effort could undoubtedly have improved the performance or found other alternatives. It appears that MIT just wasn't interested. They were mainly concerned with detection, not control. Later Houghton got tangled up in Cold War fakery, pushing for a weather control treaty because the Russkis might get there first.

“I shudder to think of the consequences of a prior Russian discovery of a feasible method of weather control,” Houghton said, although he’d previously been a voice of moderation on the plausibility of weather control. “International control of weather modification will be essential in the safety of the world as control of nuclear energy now is.”Same old story. We frame Russia for all of our evil, in order to avoid doing anything good or useful. Result: We do nothing but evil.

Labels: Patient things

American radios for home entertainment began to feature SW bands as soon as broadcasters began to provide content. SW reached a peak in WW2, when listening to the propaganda of both sides was considered part of an Informed Citizen's duties. Even some car radios had a SW band. Along the same lines, American newscasters frequently mentioned "our propaganda says .... and their propaganda says ....", trusting the American listener with the fact that both sides were stretching things.

After WW2, home radios dropped SW abruptly and picked up FM instead. This coincided with the government's sharp crackdown on 'disloyalty'. Suddenly the duty of an Informed Citizen was limited to line-of-sight propagation. Then TV finished the job, making the viewing experience line-of-sight as well. Propagandists finally fulfilled their perpetual dream: a closed pipe injecting one stream of messages from source directly to brain, with no leakage or tributary streams allowed. No skip, no bounce, no imagination. Best part: the injectees didn't even realize it was a pipe. They only knew that they couldn't stand to be disconnected from the pipe.

This state of affairs continued, with constantly tightening media monopolies and narrowing of permissible viewpoints, until the Internet came along in the mid-80s and broke the monopolies but didn't stop the censorship. The Web is, after all, a closed-circuit intercom system. Everything we see and hear passes through NSA's ears and eyes before it reaches ours.

SW isn't illegal; you can still buy SW radios designed for ham use, but they aren't meant for home entertainment. They don't look good in the living room. This limits their use to a small number of Oddballs who can be watched easily.

Why did US government and culture encourage SW in the '30s and discourage it from the '50s until the present? I think it was a question of confidence. FDR was confident that his efforts to improve America would stand comparison against the alternatives in Russia and Germany. Truman, Ike, JFK, LBJ, et al were not nearly so confident.

It's especially noteworthy that Russia was building and selling SW radios domestically in the '80s and we were not. Reagan crashed the Soviet Empire at a moment when our own empire truly would not stand comparison. As Gorby was loosening and reforming, we were eliminating industrial jobs, freezing out all possible reforms, and continually narrowing the range of permissible discourse.

Our trend has continued, with disastrous results. We don't know how the Soviet trend would have developed because it was interrupted.

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Everything in the item is still valid except the date of 1935. In fact SW was intensely used by all sorts of operators in 1930, as clearly shown in this 1930 official list. Commercial broadcasters, dispatchers for police and airlines and shipping, simulcasts of US local stations, TV and fax experiments, and above all the commercial wire services.

American radios for home entertainment began to feature SW bands as soon as broadcasters began to provide content. SW reached a peak in WW2, when listening to the propaganda of both sides was considered part of an Informed Citizen's duties. Even some car radios had a SW band. Along the same lines, American newscasters frequently mentioned "our propaganda says .... and their propaganda says ....", trusting the American listener with the fact that both sides were stretching things.

After WW2, home radios dropped SW abruptly and picked up FM instead. This coincided with the government's sharp crackdown on 'disloyalty'. Suddenly the duty of an Informed Citizen was limited to line-of-sight propagation. Then TV finished the job, making the viewing experience line-of-sight as well. Propagandists finally fulfilled their perpetual dream: a closed pipe injecting one stream of messages from source directly to brain, with no leakage or tributary streams allowed. No skip, no bounce, no imagination. Best part: the injectees didn't even realize it was a pipe. They only knew that they couldn't stand to be disconnected from the pipe.

This state of affairs continued, with constantly tightening media monopolies and narrowing of permissible viewpoints, until the Internet came along in the mid-80s and broke the monopolies but didn't stop the censorship. The Web is, after all, a closed-circuit intercom system. Everything we see and hear passes through NSA's ears and eyes before it reaches ours.

SW isn't illegal; you can still buy SW radios designed for ham use, but they aren't meant for home entertainment. They don't look good in the living room. This limits their use to a small number of Oddballs who can be watched easily.

Why did US government and culture encourage SW in the '30s and discourage it from the '50s until the present? I think it was a question of confidence. FDR was confident that his efforts to improve America would stand comparison against the alternatives in Russia and Germany. Truman, Ike, JFK, LBJ, et al were not nearly so confident.

It's especially noteworthy that Russia was building and selling SW radios domestically in the '80s and we were not. Reagan crashed the Soviet Empire at a moment when our own empire truly would not stand comparison. As Gorby was loosening and reforming, we were eliminating industrial jobs, freezing out all possible reforms, and continually narrowing the range of permissible discourse.

Our trend has continued, with disastrous results. We don't know how the Soviet trend would have developed because it was interrupted.

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Everything in the item is still valid except the date of 1935. In fact SW was intensely used by all sorts of operators in 1930, as clearly shown in this 1930 official list. Commercial broadcasters, dispatchers for police and airlines and shipping, simulcasts of US local stations, TV and fax experiments, and above all the commercial wire services.Labels: Entertainment, meta-entertainment, Natural law = Soviet law, Patient things

Labels: Morsenet of Things, Patient things

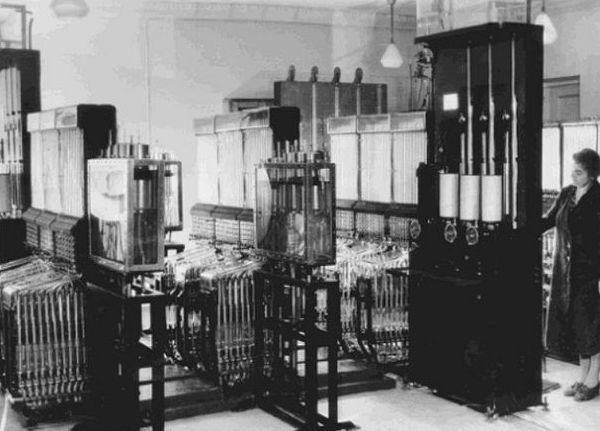

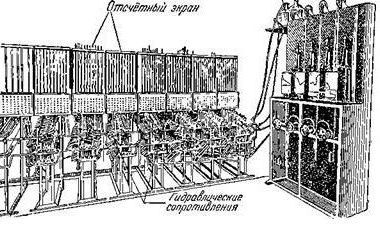

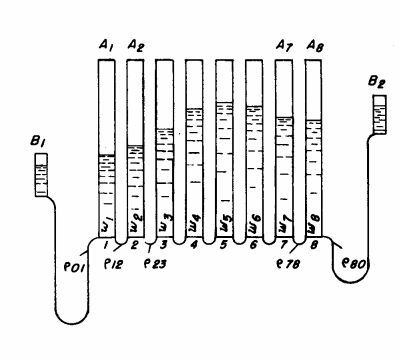

And this diagram is similar, with the plots showing up more clearly:

And this diagram is similar, with the plots showing up more clearly:

The cylinders holding graphic plots would normally be plotted outputs, but in this machine they're inputs. The real machine had four optional input variables, along with an implicit time variable.

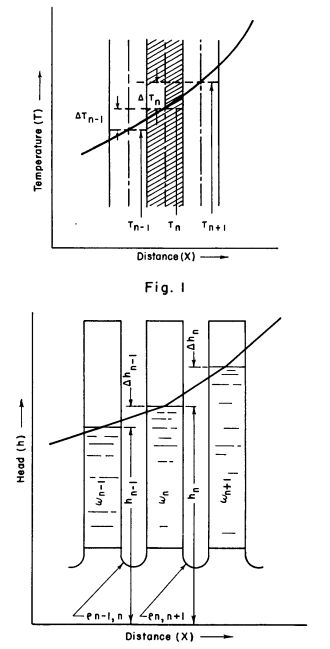

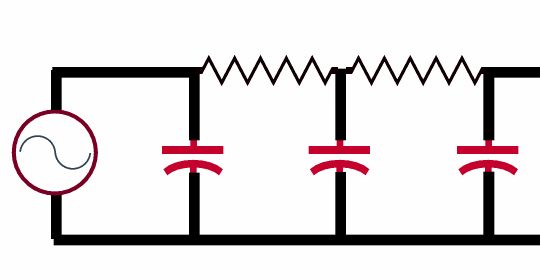

A typical use was modeling heat transfer through a structure (dam or pavement) treated as a series of layers. Each water column represented a layer, and each column could be programmed to let in water at a specific rate. In other words, each column was like an RC filter in a sequential filter setup, with the visible height (or voltage in the electronic version) representing the temperature in that layer of the dam.

The cylinders holding graphic plots would normally be plotted outputs, but in this machine they're inputs. The real machine had four optional input variables, along with an implicit time variable.

A typical use was modeling heat transfer through a structure (dam or pavement) treated as a series of layers. Each water column represented a layer, and each column could be programmed to let in water at a specific rate. In other words, each column was like an RC filter in a sequential filter setup, with the visible height (or voltage in the electronic version) representing the temperature in that layer of the dam.

These diagrams clearly show the primary advantage of analog systems, whether mechanical or fluid or electronic, over digital software. In real life each layer or module or neuron or organism is always continuously influencing all other layers, with influence and feedback in all directions at once. Interconnected water columns do it naturally. You can't do it at all with interconnected functions in software. You can pass differences from subroutine A to subroutine B, and pass results back, but there's no way to make the influences simultaneous and continuous.

Electronic version:

These diagrams clearly show the primary advantage of analog systems, whether mechanical or fluid or electronic, over digital software. In real life each layer or module or neuron or organism is always continuously influencing all other layers, with influence and feedback in all directions at once. Interconnected water columns do it naturally. You can't do it at all with interconnected functions in software. You can pass differences from subroutine A to subroutine B, and pass results back, but there's no way to make the influences simultaneous and continuous.

Electronic version:

The operator used the big lever to follow the curve already drawn on the wrapped graph. As the lever moved up and down, it moved a tank up and down, raising and lowering the 'potential voltage' input to the system. This diagram shows two input variables B1 and B2.

The operator used the big lever to follow the curve already drawn on the wrapped graph. As the lever moved up and down, it moved a tank up and down, raising and lowering the 'potential voltage' input to the system. This diagram shows two input variables B1 and B2.

Programs were entered on the three rows of valves in the center of the control panel. The description doesn't clarify the specific purpose of each row, and the upper crank is also unclear. I suspect it was a manual turner or winder for the plot cylinder, which was apparently driven by clockwork.

Programs were entered on the three rows of valves in the center of the control panel. The description doesn't clarify the specific purpose of each row, and the upper crank is also unclear. I suspect it was a manual turner or winder for the plot cylinder, which was apparently driven by clockwork.

Here Polistra is moving the big lever to follow the dam plot on the left cylinder, and the tubes are responding with a (purely imagined) output pattern. Another observer would record the heights at different times, or perhaps use a mounted movie camera to make a direct record.

The RC-like effect of the flow would also enable a single transient response to be modeled. After setting the valves for the appropriate pattern of Rs and Cs, just yank the lever upward and watch the columns move for a minute or two.

= = = = =

Footnote: The best descriptions in English are here at Archive.org.

= = = = =

Sidenote after thinking about "devices" and Pied Pipers: another advantage of mechanical and fluidic computers is independence. They can't be hacked or detected from a distance. Only a live spy in the same room can control or read them. Even electronic analogs are harder to penetrate than digital, because they don't emit a readable stream of patterned codes. An RC computer responds when you turn the knobs, then settles gradually into a new condition. No predictable and redundant patterns. Russia understood this point deeply after repeated invasions and penetrations by Krauts and Yanks.

Here Polistra is moving the big lever to follow the dam plot on the left cylinder, and the tubes are responding with a (purely imagined) output pattern. Another observer would record the heights at different times, or perhaps use a mounted movie camera to make a direct record.

The RC-like effect of the flow would also enable a single transient response to be modeled. After setting the valves for the appropriate pattern of Rs and Cs, just yank the lever upward and watch the columns move for a minute or two.

= = = = =

Footnote: The best descriptions in English are here at Archive.org.

= = = = =

Sidenote after thinking about "devices" and Pied Pipers: another advantage of mechanical and fluidic computers is independence. They can't be hacked or detected from a distance. Only a live spy in the same room can control or read them. Even electronic analogs are harder to penetrate than digital, because they don't emit a readable stream of patterned codes. An RC computer responds when you turn the knobs, then settles gradually into a new condition. No predictable and redundant patterns. Russia understood this point deeply after repeated invasions and penetrations by Krauts and Yanks.Labels: Natural law = Soviet law, Patient things

The real engineers and architects of the first 1000 were not in Github mode. They built houses and cathedrals to last, because they understood technology was not going to improve soon. The scribes put artistry into their handwritten books, knowing that the books would be used and maintained for centuries. They tried to provide beauty and pleasure for the maintainers, to insure better and longer maintenance. Bookkeepers used indelible ink on heavy paper, and 'illuminated' their ledgers with similar artistry.Providing beauty and treats for the maintainers is a lost art, but not lost for 1000 years. The practice was fairly common up to 1970 when the whole world of manufacturing and maintenance was hunted to extinction by Wall Street. Some car makers tried to create a pleasant environment for mechanics. I experienced this sort of pleasure when working on Mercedes and Toyota in the '70s. When you got into the engine compartment, everything you needed for routine maintenance was easy to find, pleasant for the eyes and hands, and satisfying to complete. I never had this experience in a VW or American car. RCA and Zenith unquestionably followed this rule with their radios in the '20s and '30s. Both brands were beautiful and entertaining outside and inside. The inside included all the info you needed, and often included specialized tools or spare parts. I try to provide moments of pleasure and beauty in my courseware and graphics. A textbook, whether on paper or software, should include some art and entertainment. I don't know if anyone appreciates them, but I feel obligated to pay back the beauty of life and nature. Later and better thought: Providing beauty and treats for the maintainers is NOT a lost art outside of human "civilization". Plants have been doing it for a billion years. Flowers and fruits are EXACTLY beauty and treats to insure maintenance.

Labels: Entertainment, Equipoise, Patient things, Smarty-plants

Labels: Parkinson, Patient things, skill-estate, Trinity House

Happy Ending: Searching Ebay for wheel charts showed surprisingly that wheel charts are still alive. They seem to be most active in graphic situations like color matching or image matching, where computers can't beat human perception. Turn the outer wheel to match the color on the object, and the inner windows show which color name or product is closest to the color.

Happy Ending: Searching Ebay for wheel charts showed surprisingly that wheel charts are still alive. They seem to be most active in graphic situations like color matching or image matching, where computers can't beat human perception. Turn the outer wheel to match the color on the object, and the inner windows show which color name or product is closest to the color.Labels: Experiential education, Happy Ending, Patient things

French telegraph poles at the time of the Foy system had a unique style. Each had a little roof and lightning rod.

French telegraph poles at the time of the Foy system had a unique style. Each had a little roof and lightning rod.

English posts at the same time also had a roof, but it was a simple wooden gable, not as stylish.

= = = = =

Also:

The Breguet clock telegraph was the universal ancestor and basis of all French systems. Was there ever an iBreguet? A pocket-watch Breguet?

Yes, at least in prototype form.

This was built and tested for military use by M. Trouvé, but apparently not adopted.

By one account the watch had two sides, like the Soviet sliderule watch. One side was turned by the knob to send, and the other side showed the incoming signal for receive.

English posts at the same time also had a roof, but it was a simple wooden gable, not as stylish.

= = = = =

Also:

The Breguet clock telegraph was the universal ancestor and basis of all French systems. Was there ever an iBreguet? A pocket-watch Breguet?

Yes, at least in prototype form.

This was built and tested for military use by M. Trouvé, but apparently not adopted.

By one account the watch had two sides, like the Soviet sliderule watch. One side was turned by the knob to send, and the other side showed the incoming signal for receive.

Another account shows a miniMorse key on the sender.

Another account shows a miniMorse key on the sender.

At that time batteries were large wet cells, so the senders and receivers were 'local remotes' from a portable central station with batteries and wire reel.

At that time batteries were large wet cells, so the senders and receivers were 'local remotes' from a portable central station with batteries and wire reel.

If I hadn't already used the title Charge of the Light Breguet, it would be more appropriate here.

If I hadn't already used the title Charge of the Light Breguet, it would be more appropriate here.Labels: Morsenet of Things, Patient things

Let 'er rip!

Let 'er rip!

A clock movement (hands on other side) powers the heavy pendulum. The pointer is forced to stay parallel, and it scans across the mysterious box line by line. When the pendulum makes contact with the 'ticker' points (just above Happystar's eyes) it energizes an electromagnet that escapes the rope pulley, allowing the mysterious box to drop one line.

What's happening inside the mysterious box?

A clock movement (hands on other side) powers the heavy pendulum. The pointer is forced to stay parallel, and it scans across the mysterious box line by line. When the pendulum makes contact with the 'ticker' points (just above Happystar's eyes) it energizes an electromagnet that escapes the rope pulley, allowing the mysterious box to drop one line.

What's happening inside the mysterious box?

A closeup view for orientation, with the pointer at the left end of the top line. The mysterious box contains a dense grid of wires running through an insulating mass like ceramic or hard wax. The top of the wires is just above the insulating surface, and the pointer gently brushes each wire as it scans. I'm showing three columns of (overly fat) wires for simplicity.

A closeup view for orientation, with the pointer at the left end of the top line. The mysterious box contains a dense grid of wires running through an insulating mass like ceramic or hard wax. The top of the wires is just above the insulating surface, and the pointer gently brushes each wire as it scans. I'm showing three columns of (overly fat) wires for simplicity.

Here's a partly transparent side view, with a slug of type touching the wires.

Here's a partly transparent side view, with a slug of type touching the wires.

The wires that are touching the protruding parts of the type or engraving are grounded. (Shown in gold here.) When the pointer hits those wires, it conducts a current through a relay, sending a pulse through the telegraph wires to the receiver.

Bain's system had one truly unique and elegant feature which hasn't been repeated in any sort of TV or scanner or printer since then. The sender and receiver were exactly the same machine. How did this work?

The wires that are touching the protruding parts of the type or engraving are grounded. (Shown in gold here.) When the pointer hits those wires, it conducts a current through a relay, sending a pulse through the telegraph wires to the receiver.

Bain's system had one truly unique and elegant feature which hasn't been repeated in any sort of TV or scanner or printer since then. The sender and receiver were exactly the same machine. How did this work?

On the receiving end, the pointer was sending current toward ground at the moments in the scan when the sending pointer had encountered a 'high point' in the engraving. In the receiver, a chemically treated paper was inserted between the wire grid and ground. The wires that received current from the pointer would cause a reaction in the dye, darkening the paper at those points.

So the sender became a receiver by inserting paper instead of an engraving. No other changes needed. ELEGANT.

The magnet on the bottom leg was used for a separate purpose, which Bain intended to be included in the scanning process. It wouldn't have worked that way. The bottom magnet was a solenoid with a little latch bolt inside.

On the receiving end, the pointer was sending current toward ground at the moments in the scan when the sending pointer had encountered a 'high point' in the engraving. In the receiver, a chemically treated paper was inserted between the wire grid and ground. The wires that received current from the pointer would cause a reaction in the dye, darkening the paper at those points.

So the sender became a receiver by inserting paper instead of an engraving. No other changes needed. ELEGANT.

The magnet on the bottom leg was used for a separate purpose, which Bain intended to be included in the scanning process. It wouldn't have worked that way. The bottom magnet was a solenoid with a little latch bolt inside.

When energized it would pop out the latch bolt and hold back the pendulum for one tick. Bain seemed to intend this as a synchronizer during the scan. This would have been messy, with some ticks used for inking and some for syncing. Heavy pendulums keep time pretty well, so it would have sufficed to run a sync session between scan sessions. Then the signals wouldn't have been confused.

When energized it would pop out the latch bolt and hold back the pendulum for one tick. Bain seemed to intend this as a synchronizer during the scan. This would have been messy, with some ticks used for inking and some for syncing. Heavy pendulums keep time pretty well, so it would have sufficed to run a sync session between scan sessions. Then the signals wouldn't have been confused.

Labels: defensible spaces, defensible times, Equipoise, Happy Ending, Morsenet of Things, Patient things

In times of chaos, it’s profoundly necessary to remember those who have come before us and the innumerable sacrifices they made. Each of these great men, whatever his individual faults, sought to live according to the Good, the True, and the Beautiful. They preserved, and they conserved.The best preservers of SKILLS, and the culture that surrounded the SKILLS, were guilds, Mutual Benefit Associations, and unions. Sometimes even governments, like the unique French preservation of semaphore skills in 1845. Too many of those Great Ones were part of the Deepstate of their time, whether the Roman Deepstate of 1000 AD, or the FBI/CIA Deepstate of 1950, or the Epstein Deepstate of 2020. In any era you have to be part of the inner elite to be widely published and remembered. The inner elite always has an evil motive. A few famous figures have pushed back the elite. Harding and FDR did it. Most of the conservative favorites were on the other side. I'm constantly trying to focus and magnify the thoughts and desires of the ungreat. Many of them didn't write books or make speeches; instead they taught or invented. Their desires and purposes come through in their patents and activities. There's a lot of purpose in a patent after you dig past the boilerplate. Three examples come to mind: Claude Chappe, Mary Jameson, Lucius Curtiss. There are billions of decent sane people in any era, most of whom deserve more credit than any of the greats or ungreats. But it's simply impossible to focus on them because they didn't leave any record at all. A few historians are trying to give them credit by writing semi-fictional stories about the ordinary peasants and parents of various eras. I don't have the skill for that work, so I'm focusing in the middle ground.

Labels: Patient people, Patient things, skill-estate

See what I mean?

The same function could have been accomplished in a much neater way by thinking in three dimensions, using Azimuth and Altitude as in telescopes or cannons. The pointer would then look like a telescope or cannon. Or a toucan.

See what I mean?

The same function could have been accomplished in a much neater way by thinking in three dimensions, using Azimuth and Altitude as in telescopes or cannons. The pointer would then look like a telescope or cannon. Or a toucan.

One of the two input signals would tick the pointer from side to side by rotating a horizontal wheel. The other input signal would tick the pointer up and down by rotating a vertical wheel.

With those two motions coordinated, the pointer could find grid locations on a square screen, or could find letters arranged in grid form.

One of the two input signals would tick the pointer from side to side by rotating a horizontal wheel. The other input signal would tick the pointer up and down by rotating a vertical wheel.

With those two motions coordinated, the pointer could find grid locations on a square screen, or could find letters arranged in grid form.

A larger version with a pencil or chalk mounted on the pointer could transmit pictures.

Later, of course, the Gray Telautograph accomplished the purpose in a strictly 2D way, again using two pulse-controlled wheels. The Telautograph became the standard way of transmitting signatures and sketches from 1890 to 1970.

[I've shown magnets that would 'flip' the ratchets forward. This probably wouldn't work well in reality; a system more like the rack and snail that drives a clock chime would have worked much better. I didn't feel like forming the more complex details needed for that setup, since this is just an imaginary reimagining of an imaginary invention.]

A larger version with a pencil or chalk mounted on the pointer could transmit pictures.

Later, of course, the Gray Telautograph accomplished the purpose in a strictly 2D way, again using two pulse-controlled wheels. The Telautograph became the standard way of transmitting signatures and sketches from 1890 to 1970.

[I've shown magnets that would 'flip' the ratchets forward. This probably wouldn't work well in reality; a system more like the rack and snail that drives a clock chime would have worked much better. I didn't feel like forming the more complex details needed for that setup, since this is just an imaginary reimagining of an imaginary invention.]

Labels: defensible times, Entertainment, Morsenet of Things, Patient things

Why is it remarkable? It uses differential action in two separate ways.

First, it guarantees that a steady flow reaches the 'drip point', using a siphon tied to a float.

Why is it remarkable? It uses differential action in two separate ways.

First, it guarantees that a steady flow reaches the 'drip point', using a siphon tied to a float.

As the water in the source tank rises and falls, a float carries a siphon. The inlet of the siphon is always below current water level, and the outlet is always inside the nearly-empty inner drip chamber. Thus the hydraulic pressure in the drip chamber remains relatively constant as you fill and empty the main source tank. (This action resembles the Willson automatic buoy.)

= = = = =

The second use of balance and equipoise is more interesting. Each drip from the inner drip chamber hits a delicately balanced spoon. When the drip hits the spoon, its weight pushes the spoon down for a moment ... until the drip exits the spoon into the lower tank. At that moment the spoon rises again. Each fall of the spoon ticks the clock forward.

As the water in the source tank rises and falls, a float carries a siphon. The inlet of the siphon is always below current water level, and the outlet is always inside the nearly-empty inner drip chamber. Thus the hydraulic pressure in the drip chamber remains relatively constant as you fill and empty the main source tank. (This action resembles the Willson automatic buoy.)

= = = = =

The second use of balance and equipoise is more interesting. Each drip from the inner drip chamber hits a delicately balanced spoon. When the drip hits the spoon, its weight pushes the spoon down for a moment ... until the drip exits the spoon into the lower tank. At that moment the spoon rises again. Each fall of the spoon ticks the clock forward.

I'm showing the ticks as minutes here for convenience, but they would probably be closer to seconds in the real thing, if it was ever built.

I'm showing the ticks as minutes here for convenience, but they would probably be closer to seconds in the real thing, if it was ever built.Labels: Equipoise, Morsenet of Things, Patient things

The authors hope that it could be used to reduce noise levels entering through an open window, while keeping homes ventilated, and could improve the health of people living in cities.Especially important now that we've temporarily and fakely REdiscovered the previously well-known value of fresh air. We won't remember the REdiscovery because we don't learn anything, but the fact remains whether we remember it or not. How do they propose to achieve the goal?

The device, assembled by Bhan Lam and colleagues, consists of 24 loudspeakers (each 4.5 cm in diameter), fixed in a grid pattern to bars attached to the inside of a window and one sensor located outside the window. If the sensor detects noise outside the building, the loudspeakers emit "anti-noise" at the same frequency as the detected noise but with inverted sound waves. This "anti-noise" cancels out the detected noise and reduces the volume of noise pollution entering the room, even when the window is open.And how much benefit do you get from this massive and wildly expensive and energy-consuming megasystem?

The authors observed up to a 10 decibel noise reduction for sounds with a frequency above 300Hz, such as traffic and train noises.10 dB isn't much. It's a barely noticeable difference in most situations. More importantly, perceptual noise reduction is only partly correlated with measured dB. Annoyance comes from several interweaving factors: The meaning of the noise (talk vs buzz, doorknock vs heating duct thump); sudden explosive sounds vs constant rumbles; and the predictability or periodicity of the pattern when not constant. A simple reduction in level for a specified frequency range can be achieved MUCH more cheaply and 'patiently' by redesigning the screen or adding louvered shutters. Some inconclusive musings on the subject. = = = = = Next day: I ran a real test of my musings and got a surprise!

Labels: Patient things

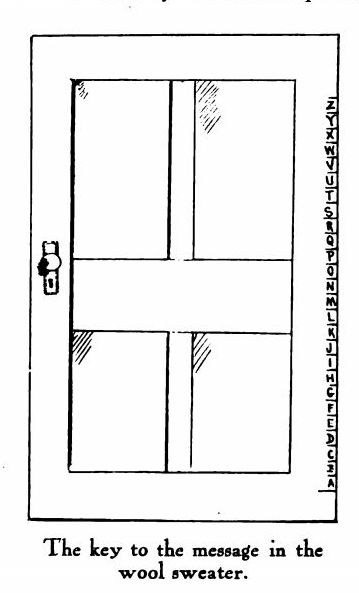

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.Labels: Equipoise, Metrology, Patient things, Real World Math

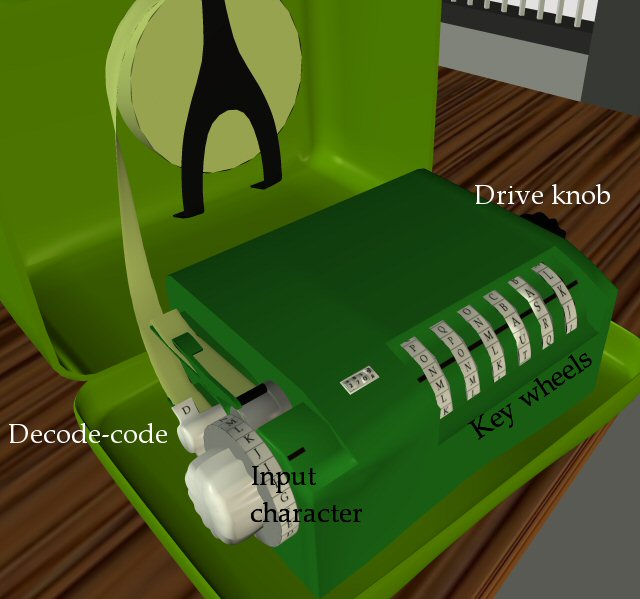

This M-209 ciphering machine was produced in great quantities during WW2. It was a small machine. Though it looks like a typewriter and has the same complexity as an adding machine, it's about the size of a landline phone.

Like the Gibson Girl transmitter,

This M-209 ciphering machine was produced in great quantities during WW2. It was a small machine. Though it looks like a typewriter and has the same complexity as an adding machine, it's about the size of a landline phone.

Like the Gibson Girl transmitter,

the M-209 was ergonomically designed to fit the soldier's body. It could be used on a desk or table, but it was mainly meant for field use. The case was indented to fit over a knee, and a strap was added to hold it to the leg.

the M-209 was ergonomically designed to fit the soldier's body. It could be used on a desk or table, but it was mainly meant for field use. The case was indented to fit over a knee, and a strap was added to hold it to the leg.

The six Key wheels on top were usually preset at headquarters before sending it out in the field. The field operator would turn the C/D switch on left to Code or Decode, then turn the Selector on left to each character of the input text and turn the black Drive knob on right. On some versions the Drive knob had a crank. As with a manual adding machine, the Drive knob would run the input letter through the cams set by the six Key wheels, and the output character would be printed on the paper tape.

The six Key wheels on top were usually preset at headquarters before sending it out in the field. The field operator would turn the C/D switch on left to Code or Decode, then turn the Selector on left to each character of the input text and turn the black Drive knob on right. On some versions the Drive knob had a crank. As with a manual adding machine, the Drive knob would run the input letter through the cams set by the six Key wheels, and the output character would be printed on the paper tape.

The M-209 was a lot like the German Enigma machine, which is famous through stories and movies. Both were based on an earlier commercial cipher machine. Stories and movies give the impression that Alan Turing was solely responsible for solving the Enigma from scratch. Turing's math probably helped, but this class of machine was common on both sides, and familiar long before the war. The British deciphering project didn't use computers or theoretical math; it just manufactured a huge number of simulator machines and ran them in mass production style, bruteforcely examining all possible combinations and permutations. When a correct key was found, the key was applied to new messages until it failed. The project was a triumph of industry and organization, not a triumph of theory.

The M-209 was a lot like the German Enigma machine, which is famous through stories and movies. Both were based on an earlier commercial cipher machine. Stories and movies give the impression that Alan Turing was solely responsible for solving the Enigma from scratch. Turing's math probably helped, but this class of machine was common on both sides, and familiar long before the war. The British deciphering project didn't use computers or theoretical math; it just manufactured a huge number of simulator machines and ran them in mass production style, bruteforcely examining all possible combinations and permutations. When a correct key was found, the key was applied to new messages until it failed. The project was a triumph of industry and organization, not a triumph of theory.Labels: Patient things

These weird-looking gadgets were fairly common in WW1. At first they were purely acoustic with no electronic parts at all. Later they continued in WW2 with more electronics.

Each unit required two soldiers, one for each pair of horns. Each pair was rotatable, but the two horns in each pair always pointed the same way. The pairs were perpendicular; one pair focused the observer on east to west, and the other focused on north to south. I'm showing only the observer for the East-West pair here. Each horn had a rubber hose at the small end, leading to the leather helmet on the observer for this pair. Observers were trained to use their binaural hearing to detect the position of an aircraft from left to right on this axis. They also estimated height and type of aircraft.

As the observers announced their estimates of position, they fed the angles into a hugely complex mechanical analog computer that assembled the estimates into an azimuth-altitude reading, which could then be applied directly to a cannon.

These weird-looking gadgets were fairly common in WW1. At first they were purely acoustic with no electronic parts at all. Later they continued in WW2 with more electronics.

Each unit required two soldiers, one for each pair of horns. Each pair was rotatable, but the two horns in each pair always pointed the same way. The pairs were perpendicular; one pair focused the observer on east to west, and the other focused on north to south. I'm showing only the observer for the East-West pair here. Each horn had a rubber hose at the small end, leading to the leather helmet on the observer for this pair. Observers were trained to use their binaural hearing to detect the position of an aircraft from left to right on this axis. They also estimated height and type of aircraft.

As the observers announced their estimates of position, they fed the angles into a hugely complex mechanical analog computer that assembled the estimates into an azimuth-altitude reading, which could then be applied directly to a cannon.

Schematic of the computer:

Schematic of the computer:

This sound locator fits into my 'patient' category because it relies on sharpened and trained and calibrated HUMAN senses. Non-patient tech weakens and atrophies human skills and senses and immunity.

Despite the experience of the engineers and the experience of the soldiers, stereo didn't break into peacetime uses until 1950.

Constant theme: Hearing matters more than vision in real life, but sound always trails far behind light in artistic and commercial development.

= = = = =

Links for Ancestral Audio so far:

Poulsen's wire recorder

The last windup phono

The Dictaphone

Dictaphone annotator.

Webster Chicago wire recorder.

Anti-aircraft sound detector

= = = = =

The Ancestral Audio set, released at ShareCG.

This sound locator fits into my 'patient' category because it relies on sharpened and trained and calibrated HUMAN senses. Non-patient tech weakens and atrophies human skills and senses and immunity.

Despite the experience of the engineers and the experience of the soldiers, stereo didn't break into peacetime uses until 1950.

Constant theme: Hearing matters more than vision in real life, but sound always trails far behind light in artistic and commercial development.

= = = = =

Links for Ancestral Audio so far:

Poulsen's wire recorder

The last windup phono

The Dictaphone

Dictaphone annotator.

Webster Chicago wire recorder.

Anti-aircraft sound detector

= = = = =

The Ancestral Audio set, released at ShareCG.

Labels: Patient things, skill-estate

Here's the fake start of renovation about two years ago:

Here's the fake start of renovation about two years ago:

And the first demo about six months ago:

And the first demo about six months ago:

Now they're FINALLY working steadily. They've closed off some windows and reshaped others, and reframed the inner walls.

This week they did something innovative, or rather inancienative.

Now they're FINALLY working steadily. They've closed off some windows and reshaped others, and reframed the inner walls.

This week they did something innovative, or rather inancienative.

They tore off the rotten old porch cover on the left and replaced it with an EXACT REPLICA of the nicer porch on the right. Respecting the original designer. My crappy picture doesn't do it justice. All the dimensions and bevels are exact.

Good work!

Random stupid thought: If copyright laws applied to architecture, this form of respect and symmetry would be illegal. According to county records this apt was built in 1923, just after the Steamboat Willie line specified by the Disney-owned copyright "law". All additions would have to be mismatched.

They tore off the rotten old porch cover on the left and replaced it with an EXACT REPLICA of the nicer porch on the right. Respecting the original designer. My crappy picture doesn't do it justice. All the dimensions and bevels are exact.

Good work!

Random stupid thought: If copyright laws applied to architecture, this form of respect and symmetry would be illegal. According to county records this apt was built in 1923, just after the Steamboat Willie line specified by the Disney-owned copyright "law". All additions would have to be mismatched.Labels: Heimatkunde, Patient things

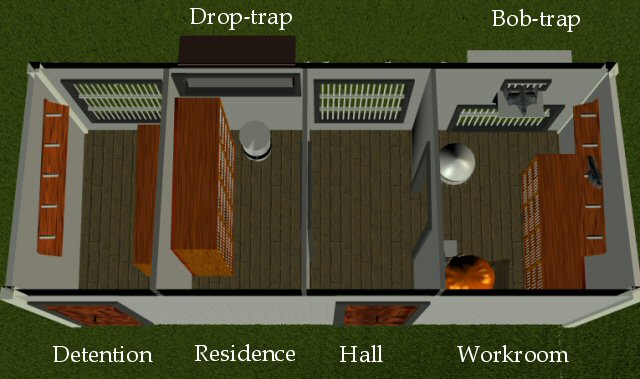

A typical military loft had three or four rooms.

A typical military loft had three or four rooms.

The Detention Cell, with a separate entrance, held misbehaving or ill pigeons. The ill birds needed to be separated because the healthy pigeons would otherwise try to kill them. Birds are Darwinians. The bad birds were kept separate so they could be retrained without affecting the others. A central hall led to a main residence and a workroom. Each room had a set of nest boxes and a set of perches.

The Detention Cell, with a separate entrance, held misbehaving or ill pigeons. The ill birds needed to be separated because the healthy pigeons would otherwise try to kill them. Birds are Darwinians. The bad birds were kept separate so they could be retrained without affecting the others. A central hall led to a main residence and a workroom. Each room had a set of nest boxes and a set of perches.

Nest boxes were just large enough for one pigeon to sleep and eat; but pigeons were generally free to fly around the rooms when not locked in for bedtime. Water and food were available in the main room.

Pigeons are a one-way communication device. When men were sent out to the field for reconnaissance or battle, they carried pigeons from the stationary loft. Sometimes they carried

in trailers,

Nest boxes were just large enough for one pigeon to sleep and eat; but pigeons were generally free to fly around the rooms when not locked in for bedtime. Water and food were available in the main room.

Pigeons are a one-way communication device. When men were sent out to the field for reconnaissance or battle, they carried pigeons from the stationary loft. Sometimes they carried

in trailers,

and sometimes in carrying cages in trucks.

and sometimes in carrying cages in trucks.

Each pigeon was equipped with a Message Capsule.

Each pigeon was equipped with a Message Capsule.

When the field unit wanted to send reports or requests for support back to headquarters, they would write a message on a standard form, roll it tightly, insert it in the capsule, and launch the pigeon. Automatic communication, no radio waves, no visible transport on the ground.

= = = = =

The one-way-ness would limit modern uses, but a Guild of modern Pigeoneers could find ways to use pigeons for off-grid banking and communication. A load of pigeons could be taken to a Branch Bank or Branch Post Office at intervals, then launched back to the central office with checks or letters. A capsule could carry massive amounts of information in digital form (eg USB stick).

= = = = =

Surprise: During WW2 the Army's pigeoneers had bred and trained two-way pigeons, or more precisely two-home pigeons. The birds knew two locations. When released at point A they would fly to point B, and when released at B they would fly to A.

When the field unit wanted to send reports or requests for support back to headquarters, they would write a message on a standard form, roll it tightly, insert it in the capsule, and launch the pigeon. Automatic communication, no radio waves, no visible transport on the ground.

= = = = =

The one-way-ness would limit modern uses, but a Guild of modern Pigeoneers could find ways to use pigeons for off-grid banking and communication. A load of pigeons could be taken to a Branch Bank or Branch Post Office at intervals, then launched back to the central office with checks or letters. A capsule could carry massive amounts of information in digital form (eg USB stick).

= = = = =

Surprise: During WW2 the Army's pigeoneers had bred and trained two-way pigeons, or more precisely two-home pigeons. The birds knew two locations. When released at point A they would fly to point B, and when released at B they would fly to A.

At Fort Monmouth a true blue-blooded pigeon named Mister Corrigan was taken, whose ancestry was known for 525 pigeon years of life. 167 famous champion racing pigeons appeared in his pedigree, including the names of some famed army message carriers. On such aristocratic material Major John K. Shawvan, of the U. S. Signal Corps, set to work. A short while ago it was announced that under the Major's tutelage Mister Corrigan had made pigeon history. He flew twelve miles from his home loft to a small container around which crouched a small group of soldiers. Five minutes later this history making pigeon was winging his way back on the return trip to the loft he had left not many minutes before. Today Fort Monmouth claims to have a flock of nearly a hundred of the only two-way homing pigeons in the world—birds able to carry messages on round trips across battlefieldsThe article also describes a similar French project in more detail. Was this line of work continued or expanded later? I can't tell from online material, but two-way pigeons are definitely possible. (Nice choice of name for the main pigeon!) I'll bet you could train for more than two locations by using an aerial picture of the uniquely marked landing zones. Show a picture of Zone C, and the bird would know how to get there. = = = = = Poser models released at ShareCG.

Labels: Patient people, Patient things

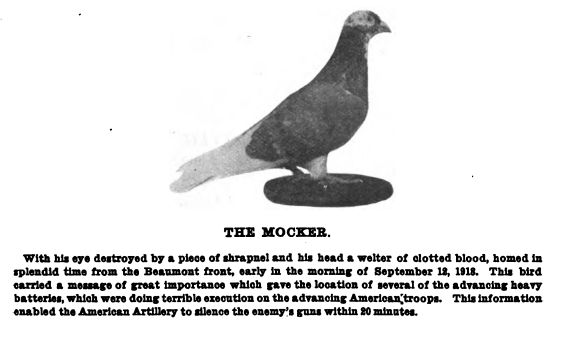

The pigeon is highly sensitive and responsive to treatment. Of great importance in this respect are kindness, firmness, and calmness of the personnel handling it, and the reward given the pigeon for good performance. The pigeon prizes its home, and every effort should be made to increase the attractiveness thereof by proper loft construction, management, and the maintenance of buildings and grounds.The Corps understood that pigeons are intelligent conscious animals with souls. Pigeons, like humans, want to be useful, want to work and accomplish a purpose. The pigeoneers knew all of their pigeons by name. Pigeons lived and served for up to 10 years, so the acquaintance was deeply personal. When a pigeon carried out its duty in extreme danger, it was commemorated by name.

Transcribed: With his eye destroyed by a piece of shrapnel and his head a welter of clotted blood, homed in splendid time from the Beaumont front, early in the morning of September 12, 1918. This bird carried a message of great importance which gave the location of several of the advancing heavy batteries, which were doing terrible execution on the advancing American troops. This information enabled the American Artillery to silence the enemy's guns within 20 minutes.

Mocker wasn't callously killed after his heroic deed; he recovered, retired, and lived at Fort Monmouth until 1937.

= = = = =

The Signal Corps also understood several physical aspects of birds that scientists were just starting to "discover" 50 years later.

Transcribed: With his eye destroyed by a piece of shrapnel and his head a welter of clotted blood, homed in splendid time from the Beaumont front, early in the morning of September 12, 1918. This bird carried a message of great importance which gave the location of several of the advancing heavy batteries, which were doing terrible execution on the advancing American troops. This information enabled the American Artillery to silence the enemy's guns within 20 minutes.

Mocker wasn't callously killed after his heroic deed; he recovered, retired, and lived at Fort Monmouth until 1937.

= = = = =

The Signal Corps also understood several physical aspects of birds that scientists were just starting to "discover" 50 years later.

The ear appears to play an important part in the sense of direction. It includes three parts, the external ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear. At the top of the inner ear there are three semicircular canals which appear to be the nerve conductors of orientation. It is possible that their great sensitiveness enables the pigeon to perceive magnetic and atmospheric impressions, and to determine the direction of the loft, either at departure or during the flight, when on account of atmospheric disturbances the bird has temporarily lost its way.Birds are blimps! Another case where we copied Nature without knowing it.

Not only do these air sacs constitute a source of supply for the lungs, but the warm air which fills them increases the buoyancy of the pigeon in the air and reduces the effort required for propulsion.And the Army also cared about the pigeoneers, and took care to select and retain them:

A careful selection must be made of pigeoneers to train and care for a loft of long-distance pigeons. The pigeoneer should have had several years of experience in other lofts, and have a marked aptitude for judging flying birds. He should be given training under another pigeoneer experienced in long-distance work until he has demonstrated his ability to train and select long-distance pigeons for himself. He must keep pigeon records meticulously, culling and eliminating unsatisfactory stock, and developing finer stock as he deems best. A qualified pigeoneer should not be required to maintain a loft containing over 50 long-distance pigeons. With these he should become intimately familiar, learning their individual characteristics in detail. He should cater to their peculiarities to bring out their best abilities; as for example, upon the return of a bird from a long-distance flight the pigeoneer assists the exhausted bird to his own perch or nest, dislodging any intruder if necessary. He should be allowed considerable latitude in exercising his initiative and developing his own ideas in regard to his birds.This is DRAMATICALLY different from the scientific approach to both pigeons and humans, developed by Skinner at the exact same time. Most scientists have continued in the Skinner mode, treating both pigeons and humans as passive identical inanimate mechanisms. The previous SOULFUL view is just starting to return in the last few years ... but only for other animals, not for humans. = = = = = Since pigeons were a form of communication device, and since pigeons are unquestionably patient by my peculiar standards, I decided to run up some of the Signal Corps pigeon equipment. First a stationary loft. These weren't manufactured by the Corps; each group of pigeoneers was expected to build its own from plans. On the left is a bob trap, a simple one-way entrance. Pigeons landed on the perch, then walked in through the swinging door. They couldn't get out again until the pigeoneer launched them.

On the right is a drop trap, nothing more than a hopper with holes. Pigeons came in for a landing and swooped in through the holes. The trap was then closed manually after all the expected flights had returned.

= = = = =

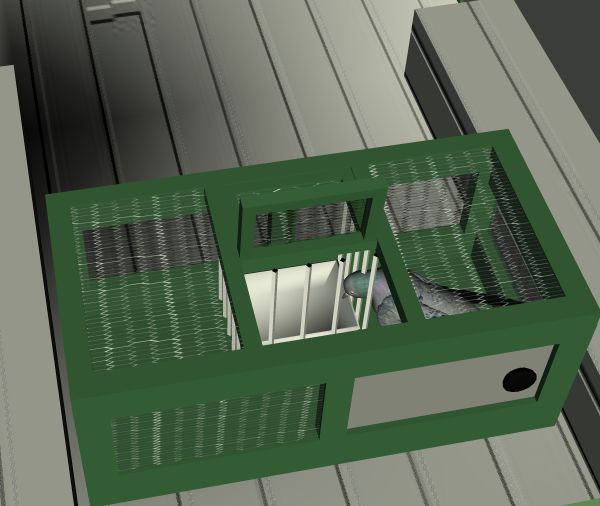

Here's a trailer loft, which was manufactured. Each trailer loft was driven to a location near the action but not at the front lines. After a week or so, the birds learned to treat the trailer as their homing point.

On the right is a drop trap, nothing more than a hopper with holes. Pigeons came in for a landing and swooped in through the holes. The trap was then closed manually after all the expected flights had returned.

= = = = =

Here's a trailer loft, which was manufactured. Each trailer loft was driven to a location near the action but not at the front lines. After a week or so, the birds learned to treat the trailer as their homing point.

Polistra is placing a feed trough, while the pigeon upstairs in the settling cage is drinking.

There's a drop trap on top, with a small landing area under it. Returning pigeons then stepped into the settling cage for rest, before the pigeoneer moved them into nests.

Polistra is placing a feed trough, while the pigeon upstairs in the settling cage is drinking.

There's a drop trap on top, with a small landing area under it. Returning pigeons then stepped into the settling cage for rest, before the pigeoneer moved them into nests.

= = = = =

As with the semaphores, I have an ulterior motive for featuring pigeons. Even after radio was mature and easy to use in WW2, there were times when radio silence was necessary. Pigeons carried the message without stirring up the ether.

Like dogs and horses, pigeons clearly have a sense of duty and mission. The pigeoneers appreciated this sense and used it respectfully.

Unlike dogs and horses, we've never used pigeons for good. We've always abused their sense of duty for war. Traditionally dogs and horses have helped us to find and cultivate our own food. Dogs helped us hunt, and got part of the meat as a reward. Horses helped us farm, and got part of the grain as a reward. Natural Law at its best. Use employees to create good value, pay the employees from the profits, respect the souls of the employees. Pigeons have served armies for thousands of years, but never carried messages for productive enterprises.

Maybe it's time to reverse the old trend.

Continued here with a few more pix and details.

= = = = =

As with the semaphores, I have an ulterior motive for featuring pigeons. Even after radio was mature and easy to use in WW2, there were times when radio silence was necessary. Pigeons carried the message without stirring up the ether.

Like dogs and horses, pigeons clearly have a sense of duty and mission. The pigeoneers appreciated this sense and used it respectfully.

Unlike dogs and horses, we've never used pigeons for good. We've always abused their sense of duty for war. Traditionally dogs and horses have helped us to find and cultivate our own food. Dogs helped us hunt, and got part of the meat as a reward. Horses helped us farm, and got part of the grain as a reward. Natural Law at its best. Use employees to create good value, pay the employees from the profits, respect the souls of the employees. Pigeons have served armies for thousands of years, but never carried messages for productive enterprises.

Maybe it's time to reverse the old trend.

Continued here with a few more pix and details.Labels: Experiential education, meta-experiential education, Patient people, Patient things