Thursday, July 02, 2020

I'm always doing Wheatstone ... but Wheatstone doesn't always work!

Second piece in Ancestral Ciphers, following (out of historical sequence) from the M-209 disk cipher machine.

In these Ancestral sets I try to find the first machine or first prototype. For ciphering, Everybody's Magazine in 1917 had a good article on early pictorial and sequential codes, p1003 of the PDF. The article was centered on Kraut ciphers, but it was really a long historical overview of the subject.

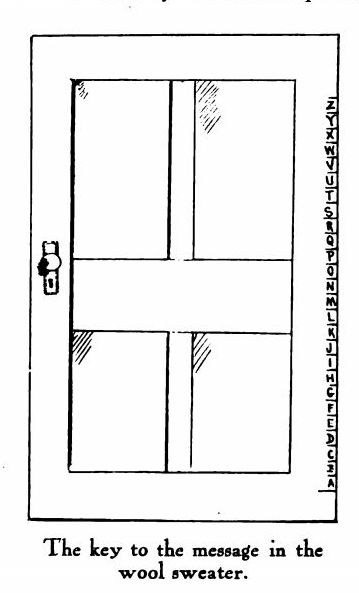

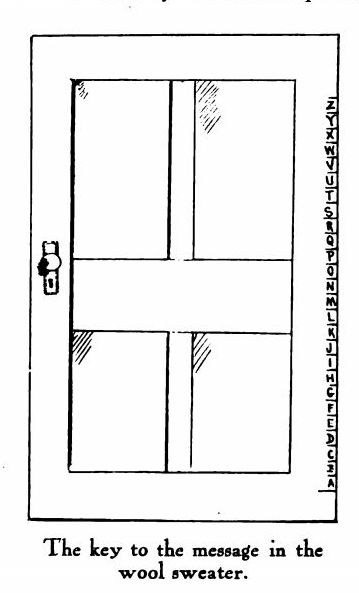

The family tree of Enigma-type machines starts with the thread cipher, often used in underground or prison communications. Sender and receiver have matching templates, sometimes homemade and linear:

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

or sometimes a page from a book or newspaper. The locations of the 26 letters are marked, ideally not in alphabetical order, and even more ideally with several duplicates of frequent letters to foil freq-count deciphering. The above picture is definitely not ideal.

Sender takes a long thread and places one end on the place in the template where the first letter of the message occurs. He then stretches the thread to the place where the second letter of the message occurs, and marks this place on the thread with ink. (Ideally disappearing ink.) He then holds that point of the thread on the location of the second letter and spans the thread to the location of the third letter of the message, and so on.

The result is a long thread with random-looking marks, or ideally no visible marks. The thread can be included easily in all sorts of items, from the classic cake to a shirt or sweater.

Sequential letter-finding guarantees difficult decryption, because each interval is the distance between previous and current letter, not a constant correlate of current letter.

Aha! Sounds like the Breguet dial telegraph. Each letter counts pulses from previous letter, and the pulse count is never directly correlated to the letter itself. Relative, not absolute.

Was there a Breguet cryptograph? Turns out that there was a device that looked and worked like Breguet, but it was invented [or claimed]** by Wheatstone.

= = = = =

Everything I

find interesting turns out to be Wheatstone, whether I know it or not.

The device is so much like the Breguet dial that I was able to reuse most of my Breguet model. I built it in a couple hours, versus a couple days for most gadgets.

Here's Polistra showing how it would have been used. Crank the main handle to input letters, and write down what the second hand shows as the ciphertext.

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

The inner circle was meant to be cardboard and temporary. The sender and receiver would be using the same randomized order for the inner circle.

Unfortunately it wouldn't have worked well. I'm pretty sure I've followed Wheatstone's description. The inner circle had one less space than the outer, and the inner hand was supposed to run slightly faster than the outer, so the phase angle between them gradually increased. After one outer circle, the inner hand should then be running 'one hour ahead' of the outer hand, then 'two hours ahead' after two outer circles, and so on.

In the first place, there's no need to have a smaller inner circle if you're going to step the inner hand forward. But more importantly, the inner hand OFTEN looks like this:

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Ambiguous. Which letter do you pick? This ambiguity would be common no matter how the ratios of inner writing and inner hand are chosen.

In fact the real (and commercially successful) Breguet setup would have done the job BETTER. Breguet was stepwise and 'digital' on both sender and receiver, with clockwork ticks and escapements, so there was never any ambiguity. Choosing and sending and printing letters is an inherently digital task. With numerical measurements you can round up or down. 3.87 becomes 4. But you can't round up or down with arbitrary symbols. A.87 doesn't become B, it's just meaningless.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Breguet could become a cryptograph by adding a 'kicker' to the receiver, so the receiver's pointer would jump ahead by 'one hour' after each revolution.

Even without any encryption, Breguet would have been frustrating for an interceptor who didn't 'tune in' at the start of the session. It could have been made much harder, even without the 'kicker', if the sender and receiver agreed to start each message from a different reset point.

= = = = =

The Hagelin multi-disk cryptograph, and its Enigma descendants, simply repeat the Wheatstone principle through several stages, with each wheel shorter ratio than the previous, so the mapping steps forward at each stage.

Here's my M-209 model made semi-transparent to show the wheel steps.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.

Wheel 1 has 26 letters, then 25, 23, 21, 19, 17. Each ratio is prime, no nice 2s or 4s.

The thread cipher, and Wheatstone's mechanized version, are relative measurements, not absolute. Wheatstone is always about relative measurement. Like the nervous system, everything is differences and deltas.

Morse and Braille and Chappe are absolute codes. Each letter, or each defined combo of letters, always has the same audio or tactile or visual pattern, starting from the same ground point. These systems can be read reliably no matter when you 'tune in'.

Morse is thus more like speech.... Or is it?

In fact speech is more like Breguet. All perception is relative and delta-based. Each vowel and consonant is judged as a transition from the previous set of frequencies.

= = = = =

** Footnote: Biographers depict Wheatstone as the typical born inventor, pouring out ideas all the time, quickly losing interest in each new idea and moving on. Some of the ideas were brilliant and original and timeless, some were unoriginal and impractical. Fortunately his business partner Charles Cooke was steady and practical, able to filter out the useful ideas and make them commercially profitable.Labels: Equipoise, Metrology, Patient things, Real World Math