Tuesday, May 26, 2020

1882 stereo

Inventions for sound are always DECADES behind inventions for vision. Other senses like smell haven't even STARTED to develop ways of recording and playing.

From an 1884 book on experimental telephones:

Sidenote: I've asked the broader question about sound vs vision dozens of times. This was probably the best answer.

Sidenote: I've asked the broader question about sound vs vision dozens of times. This was probably the best answer.

It is a common experience that, in listening at a telephone, it is practically impossible to have even a vague idea of the distance at which the person at the other end of the line appears to be. To some listeners this distance seems to be only a few yards, to others the voice apparently proceeds out of a great depth of the earth. In this case there was nothing of the kind. As soon as the experiment commenced the singers placed themselves, in the mind of the listener, at a fixed distance, some to the right and others to the left It was easy to follow their movements, and to indicate exactly, each time that they changed their position, the imaginary distance at which they appeared to be. This phenomenon, which was very curious, approximated to the theory of binauricular audition, and has never been applied, we believe, before to produce this remarkable illusion, to which may almost be given the name of auditive perspective.

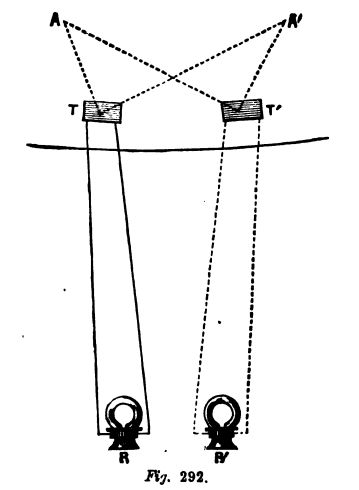

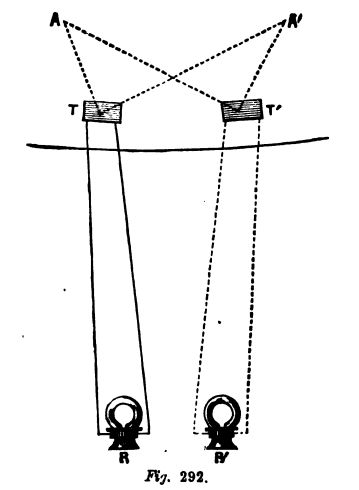

When the singer is at the point A, the transmitter T is more strongly influenced than the transmitter T' ; the left ear is, therefore, more deeply impressed than the right ear, and the singer appears to be on the left to the eight listeners of the group. When the singer is at A' the transmitter T', is more affected than the transmitter T, and the singer appears to the right of the audience; these aural impressions change with the relative positions of the singers, and their movements can in this way be followed.It's strange that the author was treating this as a mere illusion, only useful for amusement purposes. The importance of localizing sound was well understood by musicians and soldiers. Why didn't they pick up the idea immediately? The author mentioned the analogy to stereoscopes for 3d viewing, which were commercially popular then. Nothing happened until WW1, when binaural sound telescopes were used for locating a distant cannon or aircraft. After that, the idea sat dormant again until 1940 when it started to percolate into broadcasting and music recording. Stereo sound didn't go fully commercial until the mid 50s. That's a 70 year gap between idea and implementation, with NO technical barriers in the way. Unlike transistors, stereo didn't need to wait for new materials to be developed. In 1882 the telephone and the phonograph were both freshly invented. This experiment showed how to expand the telephone to stereo, and it's easy to imagine several ways to expand the phonograph. The latter would have been too large and finicky for home use, but practical for theaters. Brute force: Record two disks at the same time, then play them on two phonographs coupled together, both turned by the same clockwork. The disks would have to be 'keyed' with an extra locator hole to insure synchrony.

Sidenote: I've asked the broader question about sound vs vision dozens of times. This was probably the best answer.

Sidenote: I've asked the broader question about sound vs vision dozens of times. This was probably the best answer.Labels: Asked and badly answered, Entertainment