Thursday, May 14, 2020

Poulsen's Telegraphone

Starting a new set of 'patient tech', with a theme of Ancestral Recorders. First I've animated Valdemar Poulsen's 1902 patent for the Telegraphone or wire recorder. Next will be the Dictaphone.

Wire recorders occupy an uncomfortable spot in the history of sound-handling tech, never adopted by business or entertainment, but useful for dishonest activity.

Poulsen invented the device at a time when wax cylinder phonographs were highly popular for entertainment (play only) and for office use (record and play). Wire never dominated office use, and never made it into the home entertainment market.

I've seen and played with wax Dictaphones in storage rooms of old offices; they were still used in some offices in the '60s. I've used and owned disc recorders, which were especially popular around WW2. I've never seen a wire recorder at all, so I don't have a good feel for them.

= = = = =

The Telegraphone was meant to be used with a regular phone set to provide the microphone and earphone. Some versions placed the controls on the phone, and others connected to the phone line for remote dictation.

The dial on the front showed current location in the overall length. You could turn the two end needles inward to record only in one segment and leave other segments untouched. (A feature that never appeared on tape recorders!) The switch on right was for forward / off / backward, and the pushbutton on left was for instant stop or pause.

Poulsen's first version, which I'm using here, took special care to keep the wire strictly lined up in one layer on each reel. The reels were driven forward and backward by worm gears, so the wire always traveled straight through the fixed heads.

The dial on the front showed current location in the overall length. You could turn the two end needles inward to record only in one segment and leave other segments untouched. (A feature that never appeared on tape recorders!) The switch on right was for forward / off / backward, and the pushbutton on left was for instant stop or pause.

Poulsen's first version, which I'm using here, took special care to keep the wire strictly lined up in one layer on each reel. The reels were driven forward and backward by worm gears, so the wire always traveled straight through the fixed heads.

There was no easy way to remove the reels. This one wire was permanent. You couldn't take it off and store it or mail it. You could only dictate and listen. Adequate for ordinary dictation and transcription, but useless for archiving or distributing the audio itself.

Later on, Poulsen and other inventors found ways to keep the wire from tangling without this complexity, and found ways to remove and store pairs of reels. Still, wire never approached cylinders and discs for convenience.

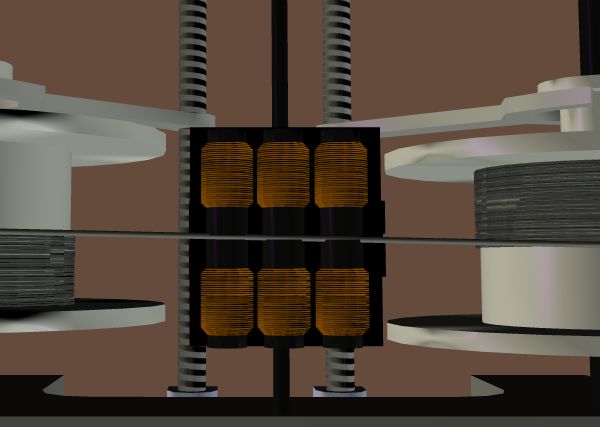

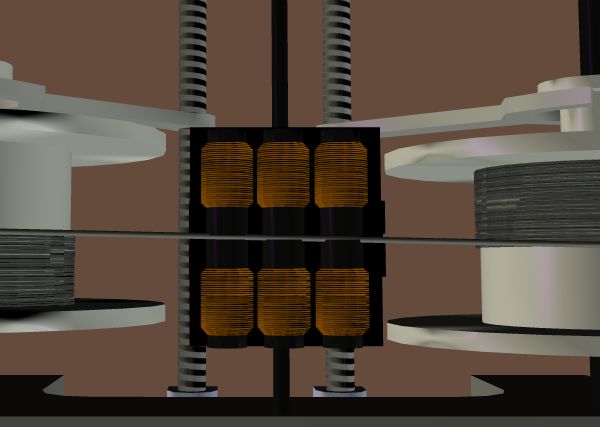

Poulsen was brute-forcish with mechanisms but brilliant with magnets. A closeup of the three heads:

There was no easy way to remove the reels. This one wire was permanent. You couldn't take it off and store it or mail it. You could only dictate and listen. Adequate for ordinary dictation and transcription, but useless for archiving or distributing the audio itself.

Later on, Poulsen and other inventors found ways to keep the wire from tangling without this complexity, and found ways to remove and store pairs of reels. Still, wire never approached cylinders and discs for convenience.

Poulsen was brute-forcish with mechanisms but brilliant with magnets. A closeup of the three heads:

Each head is actually a pair of electromagnets, with the top and bottom halves wired in series. This meant that the top and bottom sections were opposite poles as seen by the wire.

When the wire was running rightward for recording, the left head erased by forcing a constant one-way polarity, then the middle head recorded the changing waves of the incoming audio. On the return trip, the right pair erased and the middle recorded. Later versions of wire and tape recorders got rid of this unnecessary symmetry, and just recorded and played in the same direction with one erase head in front of the record/play head.

If we can believe movies and TV, wire recorders were mainly used for bugging, by police and by blackmailers. The only advantage of wire was LENGTH. A wire recorder could sit there and record for many hours without attention, while dictaphones typically ran 15 minutes and disc recorders were 5 minutes. When tape was perfected around 1950, it instantly replaced wire and disc but not Dictaphones.

= = = = =

Because I don't have hands-on experience with wire recorders, my first attempt at animating the reels failed. Looks OK until you realize that the wire is coming off both reels at once. This is why the Patent Office required physical models of inventions for many years. It's too easy to miss problems like this in a sketch. A digital animation is no better. In patents as in education, a text or drawing or software can easily misrepresent reality, but reality can't misrepresent reality.

= = = = =

Linking back to the previous set, which was interesting and meaningful from several angles. I don't think this new set will be especially interesting, but I like to keep things moving.

Summary of Ancestral Clocks.

Each head is actually a pair of electromagnets, with the top and bottom halves wired in series. This meant that the top and bottom sections were opposite poles as seen by the wire.

When the wire was running rightward for recording, the left head erased by forcing a constant one-way polarity, then the middle head recorded the changing waves of the incoming audio. On the return trip, the right pair erased and the middle recorded. Later versions of wire and tape recorders got rid of this unnecessary symmetry, and just recorded and played in the same direction with one erase head in front of the record/play head.

If we can believe movies and TV, wire recorders were mainly used for bugging, by police and by blackmailers. The only advantage of wire was LENGTH. A wire recorder could sit there and record for many hours without attention, while dictaphones typically ran 15 minutes and disc recorders were 5 minutes. When tape was perfected around 1950, it instantly replaced wire and disc but not Dictaphones.

= = = = =

Because I don't have hands-on experience with wire recorders, my first attempt at animating the reels failed. Looks OK until you realize that the wire is coming off both reels at once. This is why the Patent Office required physical models of inventions for many years. It's too easy to miss problems like this in a sketch. A digital animation is no better. In patents as in education, a text or drawing or software can easily misrepresent reality, but reality can't misrepresent reality.

= = = = =

Linking back to the previous set, which was interesting and meaningful from several angles. I don't think this new set will be especially interesting, but I like to keep things moving.

Summary of Ancestral Clocks.

The dial on the front showed current location in the overall length. You could turn the two end needles inward to record only in one segment and leave other segments untouched. (A feature that never appeared on tape recorders!) The switch on right was for forward / off / backward, and the pushbutton on left was for instant stop or pause.

Poulsen's first version, which I'm using here, took special care to keep the wire strictly lined up in one layer on each reel. The reels were driven forward and backward by worm gears, so the wire always traveled straight through the fixed heads.

The dial on the front showed current location in the overall length. You could turn the two end needles inward to record only in one segment and leave other segments untouched. (A feature that never appeared on tape recorders!) The switch on right was for forward / off / backward, and the pushbutton on left was for instant stop or pause.

Poulsen's first version, which I'm using here, took special care to keep the wire strictly lined up in one layer on each reel. The reels were driven forward and backward by worm gears, so the wire always traveled straight through the fixed heads.

There was no easy way to remove the reels. This one wire was permanent. You couldn't take it off and store it or mail it. You could only dictate and listen. Adequate for ordinary dictation and transcription, but useless for archiving or distributing the audio itself.

Later on, Poulsen and other inventors found ways to keep the wire from tangling without this complexity, and found ways to remove and store pairs of reels. Still, wire never approached cylinders and discs for convenience.

Poulsen was brute-forcish with mechanisms but brilliant with magnets. A closeup of the three heads:

There was no easy way to remove the reels. This one wire was permanent. You couldn't take it off and store it or mail it. You could only dictate and listen. Adequate for ordinary dictation and transcription, but useless for archiving or distributing the audio itself.

Later on, Poulsen and other inventors found ways to keep the wire from tangling without this complexity, and found ways to remove and store pairs of reels. Still, wire never approached cylinders and discs for convenience.

Poulsen was brute-forcish with mechanisms but brilliant with magnets. A closeup of the three heads:

Each head is actually a pair of electromagnets, with the top and bottom halves wired in series. This meant that the top and bottom sections were opposite poles as seen by the wire.

When the wire was running rightward for recording, the left head erased by forcing a constant one-way polarity, then the middle head recorded the changing waves of the incoming audio. On the return trip, the right pair erased and the middle recorded. Later versions of wire and tape recorders got rid of this unnecessary symmetry, and just recorded and played in the same direction with one erase head in front of the record/play head.

If we can believe movies and TV, wire recorders were mainly used for bugging, by police and by blackmailers. The only advantage of wire was LENGTH. A wire recorder could sit there and record for many hours without attention, while dictaphones typically ran 15 minutes and disc recorders were 5 minutes. When tape was perfected around 1950, it instantly replaced wire and disc but not Dictaphones.

= = = = =

Because I don't have hands-on experience with wire recorders, my first attempt at animating the reels failed. Looks OK until you realize that the wire is coming off both reels at once. This is why the Patent Office required physical models of inventions for many years. It's too easy to miss problems like this in a sketch. A digital animation is no better. In patents as in education, a text or drawing or software can easily misrepresent reality, but reality can't misrepresent reality.

= = = = =

Linking back to the previous set, which was interesting and meaningful from several angles. I don't think this new set will be especially interesting, but I like to keep things moving.

Summary of Ancestral Clocks.

Each head is actually a pair of electromagnets, with the top and bottom halves wired in series. This meant that the top and bottom sections were opposite poles as seen by the wire.

When the wire was running rightward for recording, the left head erased by forcing a constant one-way polarity, then the middle head recorded the changing waves of the incoming audio. On the return trip, the right pair erased and the middle recorded. Later versions of wire and tape recorders got rid of this unnecessary symmetry, and just recorded and played in the same direction with one erase head in front of the record/play head.

If we can believe movies and TV, wire recorders were mainly used for bugging, by police and by blackmailers. The only advantage of wire was LENGTH. A wire recorder could sit there and record for many hours without attention, while dictaphones typically ran 15 minutes and disc recorders were 5 minutes. When tape was perfected around 1950, it instantly replaced wire and disc but not Dictaphones.

= = = = =

Because I don't have hands-on experience with wire recorders, my first attempt at animating the reels failed. Looks OK until you realize that the wire is coming off both reels at once. This is why the Patent Office required physical models of inventions for many years. It's too easy to miss problems like this in a sketch. A digital animation is no better. In patents as in education, a text or drawing or software can easily misrepresent reality, but reality can't misrepresent reality.

= = = = =

Linking back to the previous set, which was interesting and meaningful from several angles. I don't think this new set will be especially interesting, but I like to keep things moving.

Summary of Ancestral Clocks.

Labels: Experiential education, Patient things