Wednesday, February 29, 2012

Ideas from an old book

Trying to locate more info on the nickel-iron batteries that last forever, I bumped into a wonderful old book that's fully readable in Google ebook form.

Electrical Catechism, by George Defrees Shepardson.

It's a basic intro to all aspects of electricity as known in 1901, with plenty of clear engraved illustrations and lots of plain wisdom about electricity and human nature. Written in the form of a catechism, with small questions arranged in a proper sequence for learning.

'Proper sequence' means that the learning starts with observations of common things, proceeds to an explanation of several mysteries and puzzles, and later on introduces measurements and numbers. This is the direct opposite of modern American "teaching" of math and science, which starts with numbers, ends with numbers, and ferociously avoids all possible contact with reality or facts or truth.

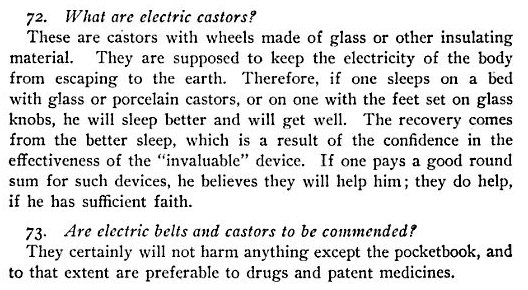

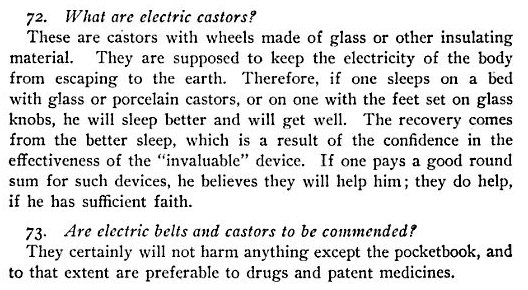

Example of wisdom: Several questions about medical electrical devices, which were common at that time.

Huge amount of wisdom and understanding packed into one paragraph! Think you'd find that much respect for common humanity in any modern science text? Hell no. You'd just get a whole chapter of scathing contempt for White-ass Bible-Thumping-ass Hetero-ass Redneck-ass Amerikkkkkkkkkkan-ass Yahoos ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha who are fucking dumb enough to believe anything ha ha ha ha ha, including the ridiculous horrible nasty idea that Carbon is not solely responsible for killing Our Beloved Fragile Sensitive Endangered Weeping Planet[pbuh]. We The Enlightened Progressive Ones know better, of course.

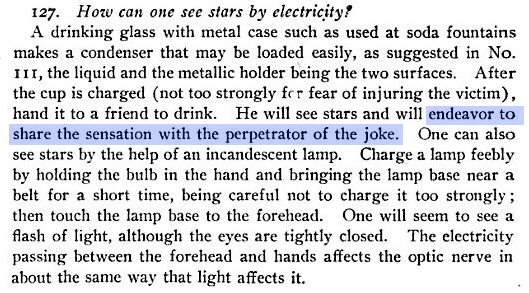

Here's an interesting experiment plus more dry wisdom:

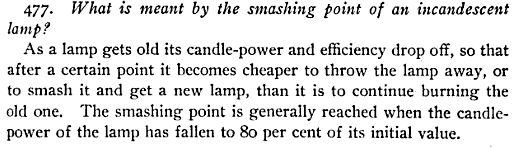

An item that sort of echoes those everlasting Edison batteries:

This seems to imply that incandescent bulbs of 1901 had an 'analog' failure pattern, asymptoting gradually toward darkness. You had to decide when the bulb had faded enough to toss it. Modern bulbs fail 'digitally': they burn out abruptly after 1000 hours. You don't get to make the decision. Remember the famous perpetual bulb in the fire station in Livermore, Calif? Installed in 1901.

= = = = =

Enough fun... I'm really trying to bring out a thought-provoking concept that seems to have been lost since 1901.

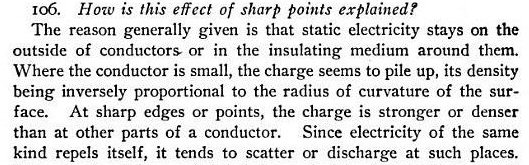

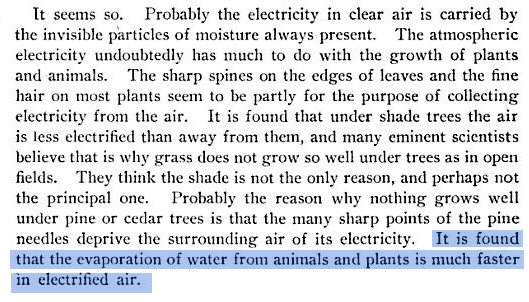

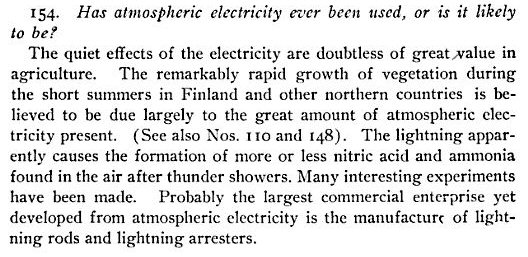

First, a basic explanation of a well-known effect:

Second, an interesting biological connection:

Third, an application of the biological connection:

The part about grass not growing under pine trees has been explained differently since then: Fallen needles are the pine's chemical weapon to prevent the encroachment of grass.

But the basic idea that plants use their points and hairs to charge/discharge is interesting and (I think) unexplored in recent times.

Compare with recent discoveries about nanowires on bacteria. When bacteria need to exchange electrons with their surroundings to create various chemical reactions, they send out little pointy-ended wires to charge or discharge.

It's certainly true that conifers like to be closer to the aurora, while broad-leaf trees prefer to be closer to the equator. It's also true, as electric power companies know only too well, that trees like to grow toward high-voltage lines.

Conifer needles are pointy and narrow, which makes them good electron transfer agents and poor absorbers of light. Conifers don't bother to shed their needles in winter, which implies they're still getting good stuff from the needles when the sun is absent. Snow is apparently part of the good stuff: Shepardson observes in a later book that uninsulated telephone wires often get charged to hundreds of volts by powdery 'dry' snow. It would appear that needles are a potent electron-gathering tool in all seasons!

Looking at this from the other angle, do conifers affect local climate? Do they suck up spare electrons from ionized air, making the air less plasma-like and less prone to thunderstorms?

Broader questions: Do all plants play a part in sunspot control of climate? Are they directly modulated by sun-influenced ionization?

Later followup here.

Electrical Catechism, by George Defrees Shepardson.

It's a basic intro to all aspects of electricity as known in 1901, with plenty of clear engraved illustrations and lots of plain wisdom about electricity and human nature. Written in the form of a catechism, with small questions arranged in a proper sequence for learning.

'Proper sequence' means that the learning starts with observations of common things, proceeds to an explanation of several mysteries and puzzles, and later on introduces measurements and numbers. This is the direct opposite of modern American "teaching" of math and science, which starts with numbers, ends with numbers, and ferociously avoids all possible contact with reality or facts or truth.

Example of wisdom: Several questions about medical electrical devices, which were common at that time.

Huge amount of wisdom and understanding packed into one paragraph! Think you'd find that much respect for common humanity in any modern science text? Hell no. You'd just get a whole chapter of scathing contempt for White-ass Bible-Thumping-ass Hetero-ass Redneck-ass Amerikkkkkkkkkkan-ass Yahoos ha ha ha ha ha ha ha ha who are fucking dumb enough to believe anything ha ha ha ha ha, including the ridiculous horrible nasty idea that Carbon is not solely responsible for killing Our Beloved Fragile Sensitive Endangered Weeping Planet[pbuh]. We The Enlightened Progressive Ones know better, of course.

Here's an interesting experiment plus more dry wisdom:

An item that sort of echoes those everlasting Edison batteries:

This seems to imply that incandescent bulbs of 1901 had an 'analog' failure pattern, asymptoting gradually toward darkness. You had to decide when the bulb had faded enough to toss it. Modern bulbs fail 'digitally': they burn out abruptly after 1000 hours. You don't get to make the decision. Remember the famous perpetual bulb in the fire station in Livermore, Calif? Installed in 1901.

= = = = =

Enough fun... I'm really trying to bring out a thought-provoking concept that seems to have been lost since 1901.

First, a basic explanation of a well-known effect:

Second, an interesting biological connection:

Third, an application of the biological connection:

The part about grass not growing under pine trees has been explained differently since then: Fallen needles are the pine's chemical weapon to prevent the encroachment of grass.

But the basic idea that plants use their points and hairs to charge/discharge is interesting and (I think) unexplored in recent times.

Compare with recent discoveries about nanowires on bacteria. When bacteria need to exchange electrons with their surroundings to create various chemical reactions, they send out little pointy-ended wires to charge or discharge.

It's certainly true that conifers like to be closer to the aurora, while broad-leaf trees prefer to be closer to the equator. It's also true, as electric power companies know only too well, that trees like to grow toward high-voltage lines.

Conifer needles are pointy and narrow, which makes them good electron transfer agents and poor absorbers of light. Conifers don't bother to shed their needles in winter, which implies they're still getting good stuff from the needles when the sun is absent. Snow is apparently part of the good stuff: Shepardson observes in a later book that uninsulated telephone wires often get charged to hundreds of volts by powdery 'dry' snow. It would appear that needles are a potent electron-gathering tool in all seasons!

Looking at this from the other angle, do conifers affect local climate? Do they suck up spare electrons from ionized air, making the air less plasma-like and less prone to thunderstorms?

Broader questions: Do all plants play a part in sunspot control of climate? Are they directly modulated by sun-influenced ionization?

Later followup here.

Labels: 20th century Dark Age, Carbon Cult