Tuesday, April 17, 2007

Each in his own tongue

Very early in this blog, I questioned whether it was better to have a common stock of knowledge, as we had 50 years ago, or to have lots of alternate sources and varieties of knowledge available. At that time I concluded, though not firmly, that the modern condition is better because there is less room for propaganda.

I've changed my mind. I was starting to write on this point a week ago, from a different viewpoint and for other reasons that I'll return to later.

But today's events make the point more critical.

[Later addendum: the "event" was the Virginia Tech massacre.]

We need a common stock of culture.

Specifically we need a commonly respectable set of cultural elements, for two reciprocal reasons.

Example.

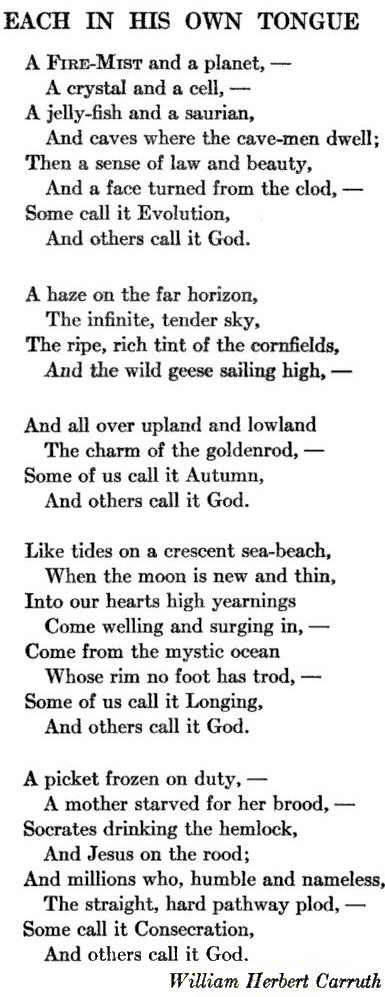

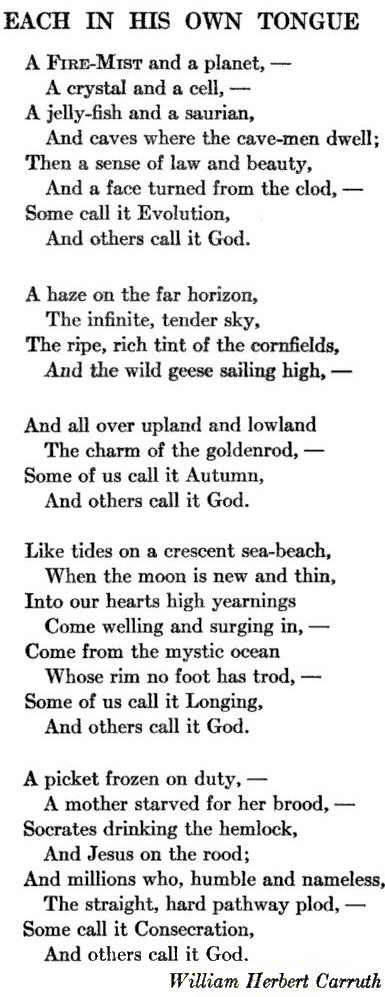

This poem was written in 1910 by an English professor at KU, and became nationally popular for a while. Its topic rings Polistra's soul, which is how I happened to locate it through Google's new and immensely valuable Books service, but the topic isn't what I'm discussing right now.

Think about it.

A poem. A nice poem. A lovely poem. A deep poem.

A poem with rhyme and rhythm.

An understandable poem.

Nationally popular.

Written by a professor of English Literature at a major university.

Nationally popular.

Nothing in this poem about bitches, hos, or Glocks, nothing about Transgressive Constructs or Endangered Elephants.

In 1910, professors and poets and artists and composers were respected because they offered something of value, something that ordinary people could recognize and enjoy. And in return, ordinary people had a common connection with fairly serious matters; when someone mentioned Ravel or Edison or Dickens, he could count on his listeners understanding the reference if not the deeper aspects of the subject.

Just after that, the Dada movement and Marxists gradually took over the 'formal' production of culture.

By 1940 the movement hadn't yet influenced most people. Modern artists were popular with the academic critics, but they were also the target of radio comedians; classical music was still commonly heard and used as material by Big Bands; newspapers still published daily poems, often by local poets.

By 1965 when I was in high school, the respect was still there, though running on vapors, but the products were already beneath contempt.

The takeover was dramatically and suddenly completed in 1969. At least symbolically, landing on the moon was the climax and endpoint of respect for learning.

Madame Mao's cultural revolution flipped the world upside down.

Now we still have 'formal' arts, but the products are at best incomprehensible and arcane, at worst obscene and deadly.

Maybe, just maybe, we'd see fewer Final Solutions to resentment and bullying if we had more respect for youngsters who try to think and create, whether in the arts or literature or science ... But we won't reach that point unless arts and literature and science become worthy of respect and worthy of common understanding.

= = = = =

Addendum:

To be clear, I'm not simply saying we need less crap in the arts and sciences. That would be a pointless recommendation. I'm talking about a cross between Gresham's and Parkinson's Law: Shit expands to fill the mental space when no gold is available. We need more gold, available, accessible, and socially approved.

In 1940, a boy with poetic or playwrightish tendencies could pick up a newspaper or turn on the radio and encounter new works, written with decency and depth. He would develop his skills by trying to copy this work, and he could envision making a career from decent writing.

In 2007, a similar boy can turn on the TV and see demonic shit. He will develop his skills and imagine his career by trying to copy this work.

Admittedly the old stuff is still available in libraries and now (blessedly) through Google Books, but it's a fact of life that young folks don't like antique stuff. They need fresh-looking material to observe and copy.

Laws and litigation are part of the modern problem. If our budding poet copies a style and publishes his work on the Web, he's likely to receive a Cease & Desist letter from Walt Disney or some other corporate content holder.

In the sciences:

In 1940, an electrically or mechanically minded boy could take apart a radio or a car; all parts were visible, adjustable and replaceable. In 2007, cars and radios are non-adjustable. No user-serviceable parts. Nothing to learn. Granted, you can still wire up 800-decibel speakers or replace your wheels with flashy '20s' to impress the hos, but it's not the same. Experimentation that leads to learning is no longer available.

Our 1940 boy with a chemical or biological flair could mix things over a Bunsen burner in his basement, or slosh around in the creek and capture odd creatures. In 2007, the budding chemist would be knocked down by a Hazmat team in spacesuits, who would proceed to evacuate the entire neighborhood permanently. The apprentice biologist would be jailed for violating the Endangered Species Act.

And what if our chemist somehow avoids the hazmat team and develops a simple compound that promises to cure cancer? Nobody will notice or fund his work, even if he's a fully credentialed professor in a medical school.

Yes, the Canadian Cancer Cure, which I've been covering here for a while, fits nicely. Stem-cell research fits the model as well. Our 'formal' and professional classes are so deeply immersed in outright fraud (global warming) and love of death (global warming again, embryonic cells) that they can't be bothered with simple and effective solutions to real problems.

Young people see this, and shape their thoughts and career plans accordingly. When golden material - decent, deep, informed by faith and rigorous thought - is visible and available, they will try to emulate the gold. When demonic shit is the only visible and marketable career path, they will pursue demonic shit.

Very early in this blog, I questioned whether it was better to have a common stock of knowledge, as we had 50 years ago, or to have lots of alternate sources and varieties of knowledge available. At that time I concluded, though not firmly, that the modern condition is better because there is less room for propaganda.

I've changed my mind. I was starting to write on this point a week ago, from a different viewpoint and for other reasons that I'll return to later.

But today's events make the point more critical.

[Later addendum: the "event" was the Virginia Tech massacre.]

We need a common stock of culture.

Specifically we need a commonly respectable set of cultural elements, for two reciprocal reasons.

Example.

This poem was written in 1910 by an English professor at KU, and became nationally popular for a while. Its topic rings Polistra's soul, which is how I happened to locate it through Google's new and immensely valuable Books service, but the topic isn't what I'm discussing right now.

Think about it.

A poem. A nice poem. A lovely poem. A deep poem.

A poem with rhyme and rhythm.

An understandable poem.

Nationally popular.

Written by a professor of English Literature at a major university.

Nationally popular.

Nothing in this poem about bitches, hos, or Glocks, nothing about Transgressive Constructs or Endangered Elephants.

In 1910, professors and poets and artists and composers were respected because they offered something of value, something that ordinary people could recognize and enjoy. And in return, ordinary people had a common connection with fairly serious matters; when someone mentioned Ravel or Edison or Dickens, he could count on his listeners understanding the reference if not the deeper aspects of the subject.

Just after that, the Dada movement and Marxists gradually took over the 'formal' production of culture.

By 1940 the movement hadn't yet influenced most people. Modern artists were popular with the academic critics, but they were also the target of radio comedians; classical music was still commonly heard and used as material by Big Bands; newspapers still published daily poems, often by local poets.

By 1965 when I was in high school, the respect was still there, though running on vapors, but the products were already beneath contempt.

The takeover was dramatically and suddenly completed in 1969. At least symbolically, landing on the moon was the climax and endpoint of respect for learning.

Madame Mao's cultural revolution flipped the world upside down.

Now we still have 'formal' arts, but the products are at best incomprehensible and arcane, at worst obscene and deadly.

Maybe, just maybe, we'd see fewer Final Solutions to resentment and bullying if we had more respect for youngsters who try to think and create, whether in the arts or literature or science ... But we won't reach that point unless arts and literature and science become worthy of respect and worthy of common understanding.

= = = = =

Addendum:

To be clear, I'm not simply saying we need less crap in the arts and sciences. That would be a pointless recommendation. I'm talking about a cross between Gresham's and Parkinson's Law: Shit expands to fill the mental space when no gold is available. We need more gold, available, accessible, and socially approved.

In 1940, a boy with poetic or playwrightish tendencies could pick up a newspaper or turn on the radio and encounter new works, written with decency and depth. He would develop his skills by trying to copy this work, and he could envision making a career from decent writing.

In 2007, a similar boy can turn on the TV and see demonic shit. He will develop his skills and imagine his career by trying to copy this work.

Admittedly the old stuff is still available in libraries and now (blessedly) through Google Books, but it's a fact of life that young folks don't like antique stuff. They need fresh-looking material to observe and copy.

Laws and litigation are part of the modern problem. If our budding poet copies a style and publishes his work on the Web, he's likely to receive a Cease & Desist letter from Walt Disney or some other corporate content holder.

In the sciences:

In 1940, an electrically or mechanically minded boy could take apart a radio or a car; all parts were visible, adjustable and replaceable. In 2007, cars and radios are non-adjustable. No user-serviceable parts. Nothing to learn. Granted, you can still wire up 800-decibel speakers or replace your wheels with flashy '20s' to impress the hos, but it's not the same. Experimentation that leads to learning is no longer available.

Our 1940 boy with a chemical or biological flair could mix things over a Bunsen burner in his basement, or slosh around in the creek and capture odd creatures. In 2007, the budding chemist would be knocked down by a Hazmat team in spacesuits, who would proceed to evacuate the entire neighborhood permanently. The apprentice biologist would be jailed for violating the Endangered Species Act.

And what if our chemist somehow avoids the hazmat team and develops a simple compound that promises to cure cancer? Nobody will notice or fund his work, even if he's a fully credentialed professor in a medical school.

Yes, the Canadian Cancer Cure, which I've been covering here for a while, fits nicely. Stem-cell research fits the model as well. Our 'formal' and professional classes are so deeply immersed in outright fraud (global warming) and love of death (global warming again, embryonic cells) that they can't be bothered with simple and effective solutions to real problems.

Young people see this, and shape their thoughts and career plans accordingly. When golden material - decent, deep, informed by faith and rigorous thought - is visible and available, they will try to emulate the gold. When demonic shit is the only visible and marketable career path, they will pursue demonic shit.