Sunday, March 15, 2020

The astonishing Hammond

The Sholes & Glidden typewriter, perfected by Remington, was first produced in 1873, and was starting to spread in 1880. Other inventors and manufacturers were trying all sorts of variations.

Let's remember the technological context of 1880. Printing was old and universal. Telegraphs and railroads were mature and common. Indoor plumbing was common in cities and nonexistent elsewhere. Telephones had just been invented and were mostly unknown. Electric power was barely experimental and wouldn't be common until 1900. Most lighting in cities was by oil or gas.

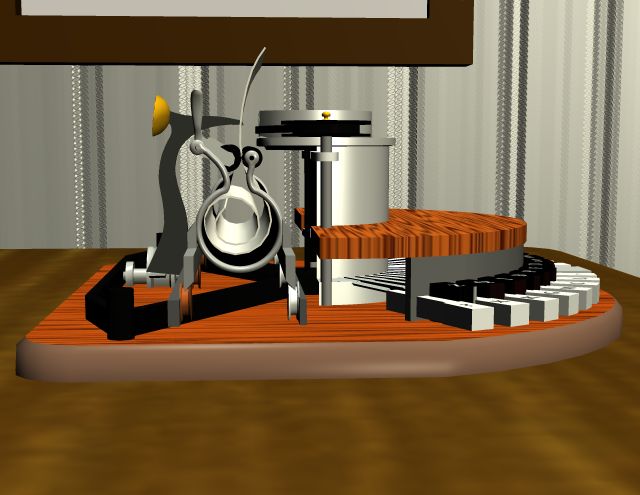

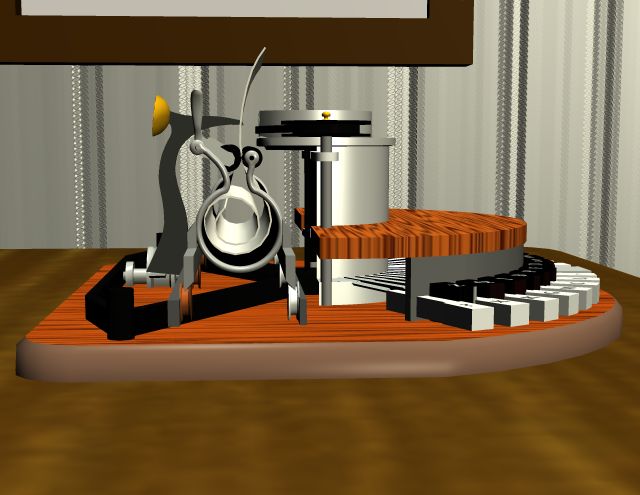

The Hammond was first patented in 1880. The single-wheel version I'm showing here was the second version in 1883. It was superior in EVERY way to the Remington, but as usual the Remington succeeded by commercial dominance, not by technical mastery.

How was the Hammond superior? Let me count the ways.

1. Long before electricity, the Hammond was power-assisted. Your fingers didn't have to power the hammers. The hammer came from behind with uniform speed and force, and pressed the paper up against the stable type. Where did the power come from? Clockwork springs driving a cam. Did you have to wind up the clockwork? No, because you rewound the spring every time you returned the carriage. Other typewriters were already using a mainspring on the carriage, to drive the stepwise spacing of the carriage itself. Hammond used the same spring to power the striking force, sparing your fingers. [Note for clarity: The curly thing below is not the mainspring. The paper came from a roll inside the cylinder, a common technique in early typewriters. Later versions used separate pieces of paper inserted separately.]

The Hammond was first patented in 1880. The single-wheel version I'm showing here was the second version in 1883. It was superior in EVERY way to the Remington, but as usual the Remington succeeded by commercial dominance, not by technical mastery.

How was the Hammond superior? Let me count the ways.

1. Long before electricity, the Hammond was power-assisted. Your fingers didn't have to power the hammers. The hammer came from behind with uniform speed and force, and pressed the paper up against the stable type. Where did the power come from? Clockwork springs driving a cam. Did you have to wind up the clockwork? No, because you rewound the spring every time you returned the carriage. Other typewriters were already using a mainspring on the carriage, to drive the stepwise spacing of the carriage itself. Hammond used the same spring to power the striking force, sparing your fingers. [Note for clarity: The curly thing below is not the mainspring. The paper came from a roll inside the cylinder, a common technique in early typewriters. Later versions used separate pieces of paper inserted separately.]

2. Because the point of impression was flat, the typeface could vary in size. Other typewriters had a cylindrical platen, which limited the size.

3. You could change the font any time you needed. The typewheel was a single small arc, easily removed and replaced. With the Remington style you needed a whole new typewriter for each size or font.

4. The typewheel had three vertical levels instead of two, and the keyboard had a Figs shift and a Caps shift. This made it possible to carry more symbols on only 30 keys, compared to the usual 44 on basic Remingtons.

2. Because the point of impression was flat, the typeface could vary in size. Other typewriters had a cylindrical platen, which limited the size.

3. You could change the font any time you needed. The typewheel was a single small arc, easily removed and replaced. With the Remington style you needed a whole new typewriter for each size or font.

4. The typewheel had three vertical levels instead of two, and the keyboard had a Figs shift and a Caps shift. This made it possible to carry more symbols on only 30 keys, compared to the usual 44 on basic Remingtons.

5. The keyboard was arranged appropriately for letter frequency, not QWERTY. Sholes and Glidden used QWERTY to avoid key collisions, but key collisions remained common on Remington-style machines. Key collisions were physically impossible on the Hammond, so there was no reason to sort the keys peculiarly. Your right fingers had the vowels and more common consonants, and your left fingers had the rest.

5. The keyboard was arranged appropriately for letter frequency, not QWERTY. Sholes and Glidden used QWERTY to avoid key collisions, but key collisions remained common on Remington-style machines. Key collisions were physically impossible on the Hammond, so there was no reason to sort the keys peculiarly. Your right fingers had the vowels and more common consonants, and your left fingers had the rest.

6. The keyboard was also less stressful for wrist and arm alignment. This advantage isn't obvious because we're unaccustomed to the arc-like keys. Look at the typist's wrists and arms to see the answer.

= = = = =

Here's a slow animation of the action with part of the covers removed.

6. The keyboard was also less stressful for wrist and arm alignment. This advantage isn't obvious because we're unaccustomed to the arc-like keys. Look at the typist's wrists and arms to see the answer.

= = = = =

Here's a slow animation of the action with part of the covers removed.

When you hit a key on the left range, the typewheel is released to turn clockwise until it hits the pin raised by the key. At that moment the hammer, also released by the key, comes forward to press the paper against the ribbon and the typewheel, hitting the chosen character squarely. When you hit a key on the right range, the typewheel is released CCW until it hits the raised pin, and the hammer does its job. [I've shown the hammer punching through the paper; not for any good educational reason; only because animating the paper would be way too hard.]

HAPPY ENDING: Like the mammals waiting for the dinosaurs to bash themselves into extinction, the Hammond found a niche and a refuge. It was renamed and repurposed as the VariTyper, and remained indispensable for offset printers and similar businesses. The VariTyper was later electrified, and the company switched over to digital until finally failing around 2007.

= = = = =

Fussy typographical footnote: The symbol on the right index key is unreadable on all the pictures I can find, from the original patent drawings to pix of antiques for sale. On the patent it looks something like a symbol I vaguely recall from typesetting:

When you hit a key on the left range, the typewheel is released to turn clockwise until it hits the pin raised by the key. At that moment the hammer, also released by the key, comes forward to press the paper against the ribbon and the typewheel, hitting the chosen character squarely. When you hit a key on the right range, the typewheel is released CCW until it hits the raised pin, and the hammer does its job. [I've shown the hammer punching through the paper; not for any good educational reason; only because animating the paper would be way too hard.]

HAPPY ENDING: Like the mammals waiting for the dinosaurs to bash themselves into extinction, the Hammond found a niche and a refuge. It was renamed and repurposed as the VariTyper, and remained indispensable for offset printers and similar businesses. The VariTyper was later electrified, and the company switched over to digital until finally failing around 2007.

= = = = =

Fussy typographical footnote: The symbol on the right index key is unreadable on all the pictures I can find, from the original patent drawings to pix of antiques for sale. On the patent it looks something like a symbol I vaguely recall from typesetting:

... (rendered in 3d for precision) ... but Google is no help in trying to locate the symbol. Since there isn't a period elsewhere on the keyboard, I put a period there for symmetry with the comma on left index. The original may have been a period with some extra indication over it for clarity? Oh. Now that I've "drawn" the symbol, I recognize it immediately. It's an eighth rest in musical notation, which certainly wouldn't be in a prominent position on a typewriter! So the original is still mysterious, but a period is most likely by symmetry. Everything on the Hammond is organically symmetrical and differential.

Unsurprising: When the symbol was floating around in what remains of my brain, I couldn't place it. After running it through some muscles and senses, I could place it. Experiential education as always.

... (rendered in 3d for precision) ... but Google is no help in trying to locate the symbol. Since there isn't a period elsewhere on the keyboard, I put a period there for symmetry with the comma on left index. The original may have been a period with some extra indication over it for clarity? Oh. Now that I've "drawn" the symbol, I recognize it immediately. It's an eighth rest in musical notation, which certainly wouldn't be in a prominent position on a typewriter! So the original is still mysterious, but a period is most likely by symmetry. Everything on the Hammond is organically symmetrical and differential.

Unsurprising: When the symbol was floating around in what remains of my brain, I couldn't place it. After running it through some muscles and senses, I could place it. Experiential education as always.

The Hammond was first patented in 1880. The single-wheel version I'm showing here was the second version in 1883. It was superior in EVERY way to the Remington, but as usual the Remington succeeded by commercial dominance, not by technical mastery.

How was the Hammond superior? Let me count the ways.

1. Long before electricity, the Hammond was power-assisted. Your fingers didn't have to power the hammers. The hammer came from behind with uniform speed and force, and pressed the paper up against the stable type. Where did the power come from? Clockwork springs driving a cam. Did you have to wind up the clockwork? No, because you rewound the spring every time you returned the carriage. Other typewriters were already using a mainspring on the carriage, to drive the stepwise spacing of the carriage itself. Hammond used the same spring to power the striking force, sparing your fingers. [Note for clarity: The curly thing below is not the mainspring. The paper came from a roll inside the cylinder, a common technique in early typewriters. Later versions used separate pieces of paper inserted separately.]

The Hammond was first patented in 1880. The single-wheel version I'm showing here was the second version in 1883. It was superior in EVERY way to the Remington, but as usual the Remington succeeded by commercial dominance, not by technical mastery.

How was the Hammond superior? Let me count the ways.

1. Long before electricity, the Hammond was power-assisted. Your fingers didn't have to power the hammers. The hammer came from behind with uniform speed and force, and pressed the paper up against the stable type. Where did the power come from? Clockwork springs driving a cam. Did you have to wind up the clockwork? No, because you rewound the spring every time you returned the carriage. Other typewriters were already using a mainspring on the carriage, to drive the stepwise spacing of the carriage itself. Hammond used the same spring to power the striking force, sparing your fingers. [Note for clarity: The curly thing below is not the mainspring. The paper came from a roll inside the cylinder, a common technique in early typewriters. Later versions used separate pieces of paper inserted separately.]

2. Because the point of impression was flat, the typeface could vary in size. Other typewriters had a cylindrical platen, which limited the size.

3. You could change the font any time you needed. The typewheel was a single small arc, easily removed and replaced. With the Remington style you needed a whole new typewriter for each size or font.

4. The typewheel had three vertical levels instead of two, and the keyboard had a Figs shift and a Caps shift. This made it possible to carry more symbols on only 30 keys, compared to the usual 44 on basic Remingtons.

2. Because the point of impression was flat, the typeface could vary in size. Other typewriters had a cylindrical platen, which limited the size.

3. You could change the font any time you needed. The typewheel was a single small arc, easily removed and replaced. With the Remington style you needed a whole new typewriter for each size or font.

4. The typewheel had three vertical levels instead of two, and the keyboard had a Figs shift and a Caps shift. This made it possible to carry more symbols on only 30 keys, compared to the usual 44 on basic Remingtons.

5. The keyboard was arranged appropriately for letter frequency, not QWERTY. Sholes and Glidden used QWERTY to avoid key collisions, but key collisions remained common on Remington-style machines. Key collisions were physically impossible on the Hammond, so there was no reason to sort the keys peculiarly. Your right fingers had the vowels and more common consonants, and your left fingers had the rest.

5. The keyboard was arranged appropriately for letter frequency, not QWERTY. Sholes and Glidden used QWERTY to avoid key collisions, but key collisions remained common on Remington-style machines. Key collisions were physically impossible on the Hammond, so there was no reason to sort the keys peculiarly. Your right fingers had the vowels and more common consonants, and your left fingers had the rest.

6. The keyboard was also less stressful for wrist and arm alignment. This advantage isn't obvious because we're unaccustomed to the arc-like keys. Look at the typist's wrists and arms to see the answer.

= = = = =

Here's a slow animation of the action with part of the covers removed.

6. The keyboard was also less stressful for wrist and arm alignment. This advantage isn't obvious because we're unaccustomed to the arc-like keys. Look at the typist's wrists and arms to see the answer.

= = = = =

Here's a slow animation of the action with part of the covers removed.

When you hit a key on the left range, the typewheel is released to turn clockwise until it hits the pin raised by the key. At that moment the hammer, also released by the key, comes forward to press the paper against the ribbon and the typewheel, hitting the chosen character squarely. When you hit a key on the right range, the typewheel is released CCW until it hits the raised pin, and the hammer does its job. [I've shown the hammer punching through the paper; not for any good educational reason; only because animating the paper would be way too hard.]

HAPPY ENDING: Like the mammals waiting for the dinosaurs to bash themselves into extinction, the Hammond found a niche and a refuge. It was renamed and repurposed as the VariTyper, and remained indispensable for offset printers and similar businesses. The VariTyper was later electrified, and the company switched over to digital until finally failing around 2007.

= = = = =

Fussy typographical footnote: The symbol on the right index key is unreadable on all the pictures I can find, from the original patent drawings to pix of antiques for sale. On the patent it looks something like a symbol I vaguely recall from typesetting:

When you hit a key on the left range, the typewheel is released to turn clockwise until it hits the pin raised by the key. At that moment the hammer, also released by the key, comes forward to press the paper against the ribbon and the typewheel, hitting the chosen character squarely. When you hit a key on the right range, the typewheel is released CCW until it hits the raised pin, and the hammer does its job. [I've shown the hammer punching through the paper; not for any good educational reason; only because animating the paper would be way too hard.]

HAPPY ENDING: Like the mammals waiting for the dinosaurs to bash themselves into extinction, the Hammond found a niche and a refuge. It was renamed and repurposed as the VariTyper, and remained indispensable for offset printers and similar businesses. The VariTyper was later electrified, and the company switched over to digital until finally failing around 2007.

= = = = =

Fussy typographical footnote: The symbol on the right index key is unreadable on all the pictures I can find, from the original patent drawings to pix of antiques for sale. On the patent it looks something like a symbol I vaguely recall from typesetting:

... (rendered in 3d for precision) ... but Google is no help in trying to locate the symbol. Since there isn't a period elsewhere on the keyboard, I put a period there for symmetry with the comma on left index. The original may have been a period with some extra indication over it for clarity? Oh. Now that I've "drawn" the symbol, I recognize it immediately. It's an eighth rest in musical notation, which certainly wouldn't be in a prominent position on a typewriter! So the original is still mysterious, but a period is most likely by symmetry. Everything on the Hammond is organically symmetrical and differential.

Unsurprising: When the symbol was floating around in what remains of my brain, I couldn't place it. After running it through some muscles and senses, I could place it. Experiential education as always.

... (rendered in 3d for precision) ... but Google is no help in trying to locate the symbol. Since there isn't a period elsewhere on the keyboard, I put a period there for symmetry with the comma on left index. The original may have been a period with some extra indication over it for clarity? Oh. Now that I've "drawn" the symbol, I recognize it immediately. It's an eighth rest in musical notation, which certainly wouldn't be in a prominent position on a typewriter! So the original is still mysterious, but a period is most likely by symmetry. Everything on the Hammond is organically symmetrical and differential.

Unsurprising: When the symbol was floating around in what remains of my brain, I couldn't place it. After running it through some muscles and senses, I could place it. Experiential education as always.Labels: Happy Ending, Morsenet of Things, Patient things