Tuesday, January 19, 2021

Hartness to Mont-gros, back to Hartness.

When I don't understand how something works, I build it. With electronic stuff I can build the real thing using tubes and transistors and capacitors and so on. With mechanical stuff I don't have the needed skills or tools or workspace, so I have to "build" it and animate it digitally.

I had previously focused on the Altitude-Azimuth way of reaching all available angles. When I read about the Hartness scope, I realized there were other systems. The Hartness scope itself was a mystery, so I followed his discussions and started with the two other equatorial scopes.

Rehashing the relevant parts of the Mont-gros item:

= = = = = START REPRINT:

This bit of graphics started from thinking about James Hartness, the semi-pro astronomer who became governor of Vermont in the '20s. Hartness invented a specialized form of telescope that enabled him to stay comfortably inside, without having to pivot around with the end of the scope.

I didn't understand how this worked, so I started looking it up. Turns out he didn't invent it. The system is called the Equatorial coudé or bent equatorial, and it was invented by Maurice Loewy in 1871. Loewy was a detail-oriented astronomer who spent his career compiling and editing tables and books of star locations and star photographs. Hartness himself, writing about his variation on Loewy, gave proper credit to Loewy. The claim of invention was only in popular magazine features about the telescope.

= = = = =

But why was it needed and how did it work?

One of the best known coudé scopes was at Mont-gros, an observatory in Monaco.

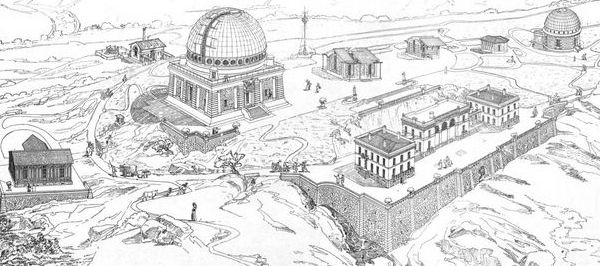

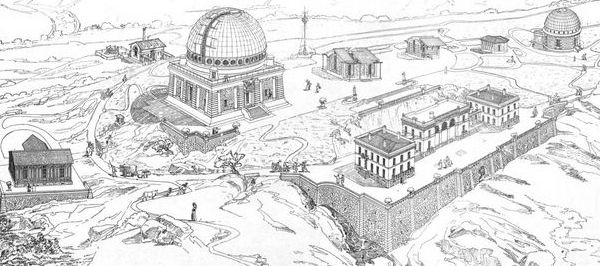

Here's the real Mont-gros around 1890:

I didn't understand how this worked, so I started looking it up. Turns out he didn't invent it. The system is called the Equatorial coudé or bent equatorial, and it was invented by Maurice Loewy in 1871. Loewy was a detail-oriented astronomer who spent his career compiling and editing tables and books of star locations and star photographs. Hartness himself, writing about his variation on Loewy, gave proper credit to Loewy. The claim of invention was only in popular magazine features about the telescope.

= = = = =

But why was it needed and how did it work?

One of the best known coudé scopes was at Mont-gros, an observatory in Monaco.

Here's the real Mont-gros around 1890:

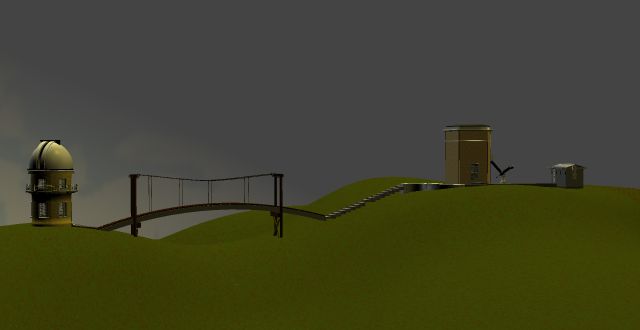

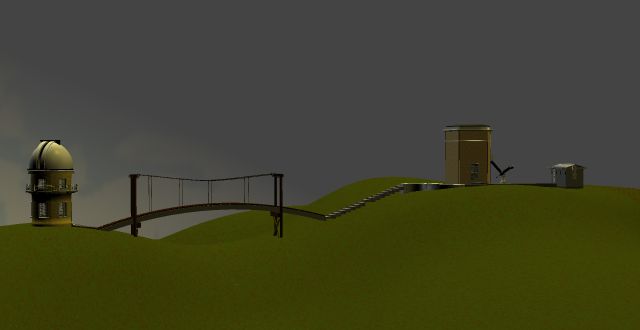

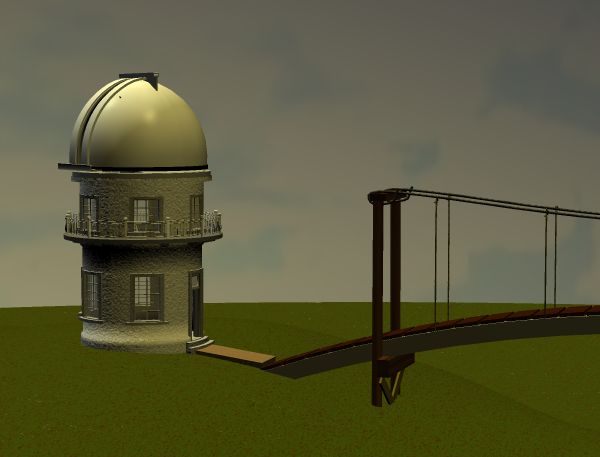

My abbreviated version represents only the three buildings at the right end of the overview. (The big central observatory has already been modeled in the realm of Google Sketchup, so I didn't need or want to duplicate it.)

My abbreviated version represents only the three buildings at the right end of the overview. (The big central observatory has already been modeled in the realm of Google Sketchup, so I didn't need or want to duplicate it.)

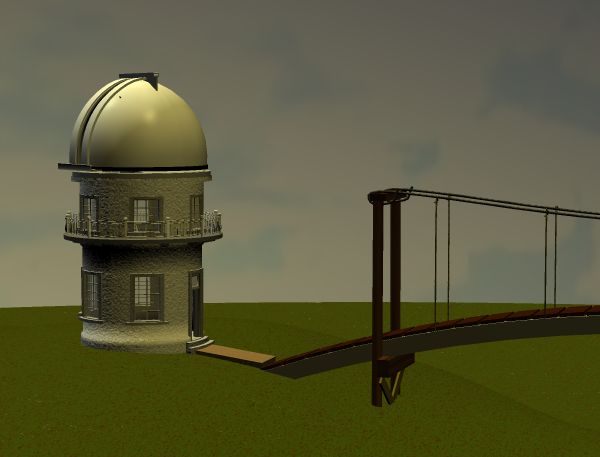

From left, the Coupole Schmausser, the coudé, and a small building housing a sidereal transit.

From left, the Coupole Schmausser, the coudé, and a small building housing a sidereal transit.

The Coupole still exists.

The Coupole still exists.

As does the coudé.

As does the coudé.

This small building is no longer there, judging by various pix.

= = = = =

The coudé was specialized from a more general Equatorial. The Equatorial reaches all parts of the sky in a peculiar way, unlike the more ordinary and understandable Altitude and Azimuth system. Here we run the Equatorial through all of its gyrations, with Happystar desperately trying to hold on and observe.

This small building is no longer there, judging by various pix.

= = = = =

The coudé was specialized from a more general Equatorial. The Equatorial reaches all parts of the sky in a peculiar way, unlike the more ordinary and understandable Altitude and Azimuth system. Here we run the Equatorial through all of its gyrations, with Happystar desperately trying to hold on and observe.

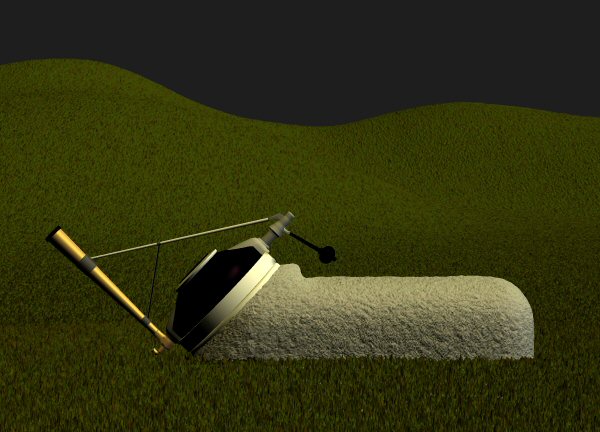

The coudé runs through the same pattern, reaching all angles of the sky, but it's bent (coudé) in the middle with two mirrors. The bend enables the eyepiece to remain in one place, so it can pass through a single weatherstripped hole in a wall without needing a rotating dome or a retractable cover. The astronomer can stay in one chair, comfortably heated or cooled, unhassled by birds or bugs, while the business end of the scope remains outside with no thermal differences to distort the air.

The coudé runs through the same pattern, reaching all angles of the sky, but it's bent (coudé) in the middle with two mirrors. The bend enables the eyepiece to remain in one place, so it can pass through a single weatherstripped hole in a wall without needing a rotating dome or a retractable cover. The astronomer can stay in one chair, comfortably heated or cooled, unhassled by birds or bugs, while the business end of the scope remains outside with no thermal differences to distort the air.

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Now I can finally return to the Hartness scope itself. He described its advantages and disadvantages clearly, but the mechanism still didn't look like it could even move. After studying his wonderfully clear patent, I finally grasped it well enough to animate it.

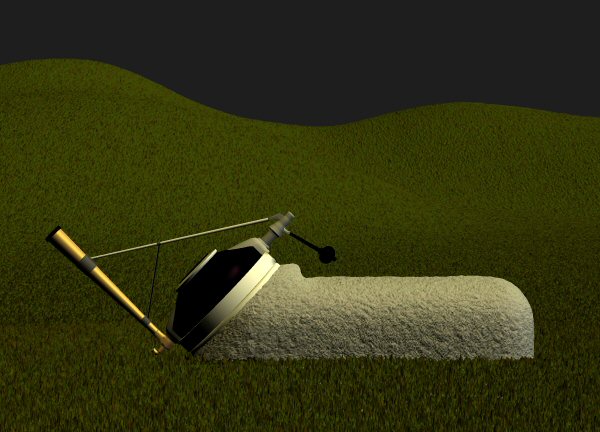

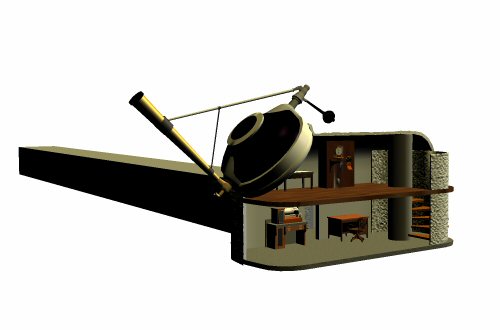

Here's an outer view of the mostly underground chamber:

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Now I can finally return to the Hartness scope itself. He described its advantages and disadvantages clearly, but the mechanism still didn't look like it could even move. After studying his wonderfully clear patent, I finally grasped it well enough to animate it.

Here's an outer view of the mostly underground chamber:

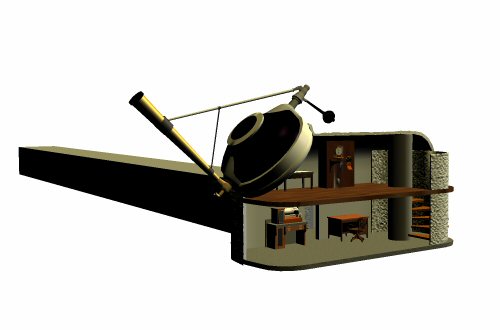

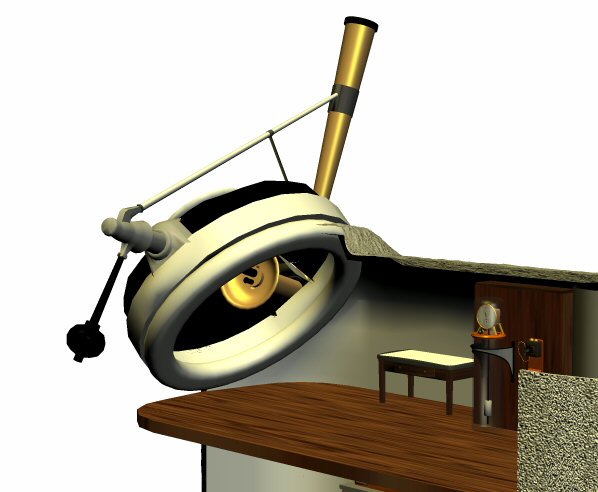

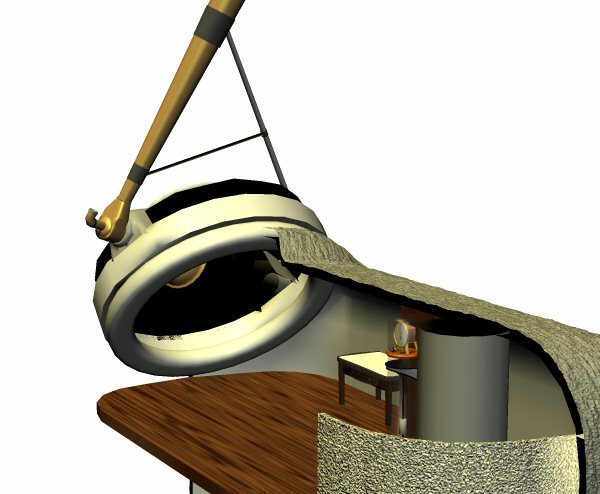

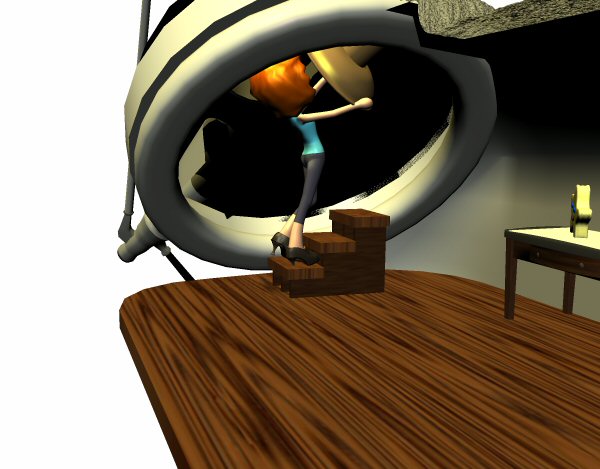

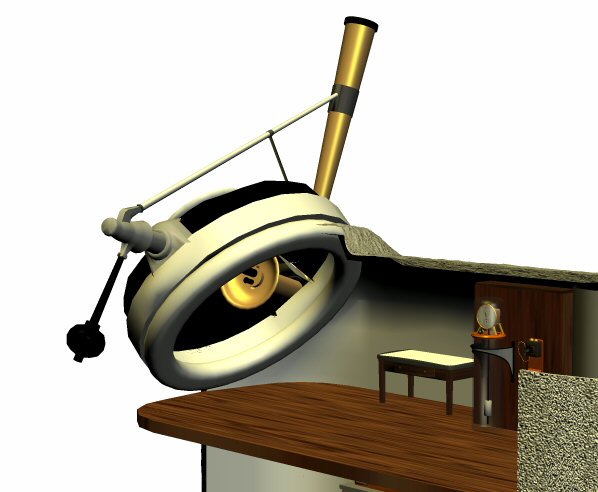

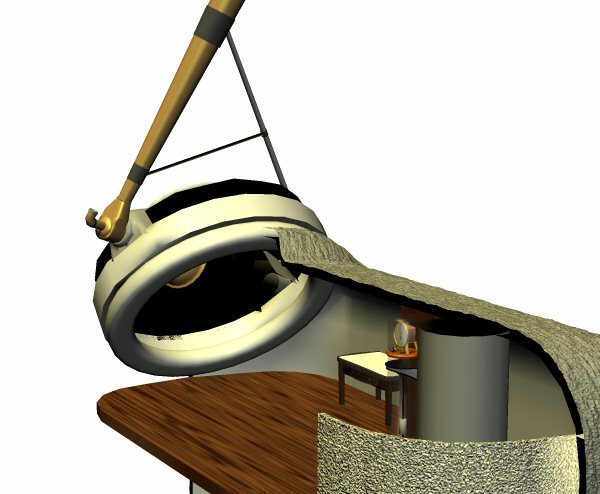

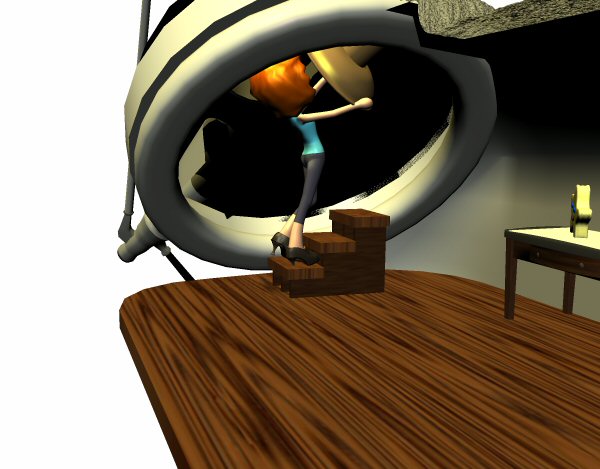

And various inner views. The upper floor was the scope workspace, and the lower floor was for calculating and recording. The long tunnel leads back to the Hartness mansion.

And various inner views. The upper floor was the scope workspace, and the lower floor was for calculating and recording. The long tunnel leads back to the Hartness mansion.

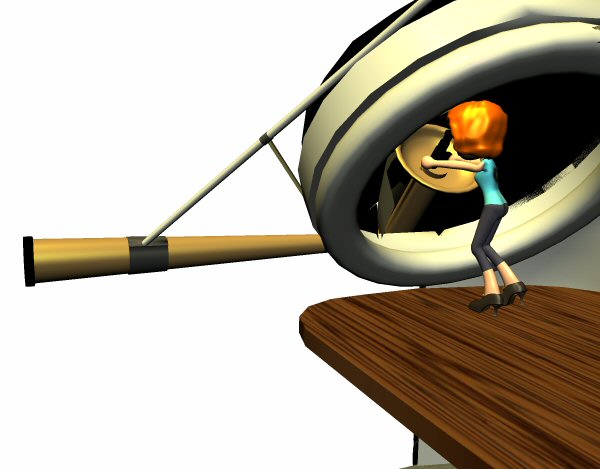

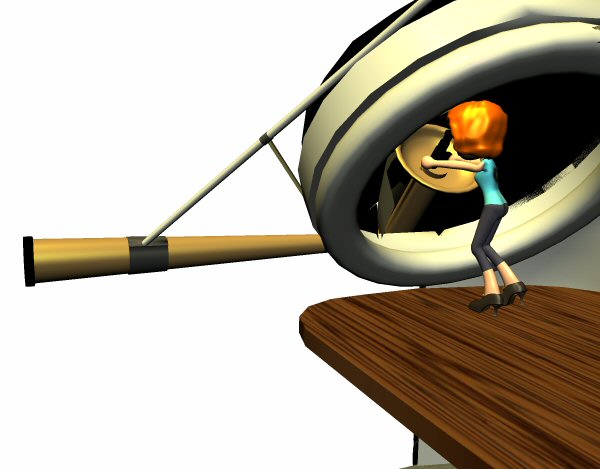

Now animate, showing the two separate motions and the eyepiece wandering all over the place with Happystar hanging on and trying to observe:

Now animate, showing the two separate motions and the eyepiece wandering all over the place with Happystar hanging on and trying to observe:

After animating it, I can see the pros and cons, and it seems to me that the cons outweigh the pros. Hartness eliminated one of the two mirrors in the equatorial coudé, and expanded the range of available angles somewhat, but he lost the stable eyepiece. His version is certainly less mobile than the simple Altitude-Azimuth scope. The astronomer can stand in one small area, but he still has to move around and look up and down and sideways, in often uncomfortable or painful angles.

After animating it, I can see the pros and cons, and it seems to me that the cons outweigh the pros. Hartness eliminated one of the two mirrors in the equatorial coudé, and expanded the range of available angles somewhat, but he lost the stable eyepiece. His version is certainly less mobile than the simple Altitude-Azimuth scope. The astronomer can stand in one small area, but he still has to move around and look up and down and sideways, in often uncomfortable or painful angles.

Hartness could have regained the perfectly still eyepiece while retaining the expanded range, by adding another mirror like this:

Hartness could have regained the perfectly still eyepiece while retaining the expanded range, by adding another mirror like this:

It's not clear why he didn't add this extra angle.

It's not clear why he didn't add this extra angle.

I didn't understand how this worked, so I started looking it up. Turns out he didn't invent it. The system is called the Equatorial coudé or bent equatorial, and it was invented by Maurice Loewy in 1871. Loewy was a detail-oriented astronomer who spent his career compiling and editing tables and books of star locations and star photographs. Hartness himself, writing about his variation on Loewy, gave proper credit to Loewy. The claim of invention was only in popular magazine features about the telescope.

= = = = =

But why was it needed and how did it work?

One of the best known coudé scopes was at Mont-gros, an observatory in Monaco.

Here's the real Mont-gros around 1890:

I didn't understand how this worked, so I started looking it up. Turns out he didn't invent it. The system is called the Equatorial coudé or bent equatorial, and it was invented by Maurice Loewy in 1871. Loewy was a detail-oriented astronomer who spent his career compiling and editing tables and books of star locations and star photographs. Hartness himself, writing about his variation on Loewy, gave proper credit to Loewy. The claim of invention was only in popular magazine features about the telescope.

= = = = =

But why was it needed and how did it work?

One of the best known coudé scopes was at Mont-gros, an observatory in Monaco.

Here's the real Mont-gros around 1890:

My abbreviated version represents only the three buildings at the right end of the overview. (The big central observatory has already been modeled in the realm of Google Sketchup, so I didn't need or want to duplicate it.)

My abbreviated version represents only the three buildings at the right end of the overview. (The big central observatory has already been modeled in the realm of Google Sketchup, so I didn't need or want to duplicate it.)

From left, the Coupole Schmausser, the coudé, and a small building housing a sidereal transit.

From left, the Coupole Schmausser, the coudé, and a small building housing a sidereal transit.

The Coupole still exists.

The Coupole still exists.

As does the coudé.

As does the coudé.

This small building is no longer there, judging by various pix.

= = = = =

The coudé was specialized from a more general Equatorial. The Equatorial reaches all parts of the sky in a peculiar way, unlike the more ordinary and understandable Altitude and Azimuth system. Here we run the Equatorial through all of its gyrations, with Happystar desperately trying to hold on and observe.

This small building is no longer there, judging by various pix.

= = = = =

The coudé was specialized from a more general Equatorial. The Equatorial reaches all parts of the sky in a peculiar way, unlike the more ordinary and understandable Altitude and Azimuth system. Here we run the Equatorial through all of its gyrations, with Happystar desperately trying to hold on and observe.

The coudé runs through the same pattern, reaching all angles of the sky, but it's bent (coudé) in the middle with two mirrors. The bend enables the eyepiece to remain in one place, so it can pass through a single weatherstripped hole in a wall without needing a rotating dome or a retractable cover. The astronomer can stay in one chair, comfortably heated or cooled, unhassled by birds or bugs, while the business end of the scope remains outside with no thermal differences to distort the air.

The coudé runs through the same pattern, reaching all angles of the sky, but it's bent (coudé) in the middle with two mirrors. The bend enables the eyepiece to remain in one place, so it can pass through a single weatherstripped hole in a wall without needing a rotating dome or a retractable cover. The astronomer can stay in one chair, comfortably heated or cooled, unhassled by birds or bugs, while the business end of the scope remains outside with no thermal differences to distort the air.

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Now I can finally return to the Hartness scope itself. He described its advantages and disadvantages clearly, but the mechanism still didn't look like it could even move. After studying his wonderfully clear patent, I finally grasped it well enough to animate it.

Here's an outer view of the mostly underground chamber:

= = = = = END REPRINT.

Now I can finally return to the Hartness scope itself. He described its advantages and disadvantages clearly, but the mechanism still didn't look like it could even move. After studying his wonderfully clear patent, I finally grasped it well enough to animate it.

Here's an outer view of the mostly underground chamber:

And various inner views. The upper floor was the scope workspace, and the lower floor was for calculating and recording. The long tunnel leads back to the Hartness mansion.

And various inner views. The upper floor was the scope workspace, and the lower floor was for calculating and recording. The long tunnel leads back to the Hartness mansion.

Now animate, showing the two separate motions and the eyepiece wandering all over the place with Happystar hanging on and trying to observe:

Now animate, showing the two separate motions and the eyepiece wandering all over the place with Happystar hanging on and trying to observe:

After animating it, I can see the pros and cons, and it seems to me that the cons outweigh the pros. Hartness eliminated one of the two mirrors in the equatorial coudé, and expanded the range of available angles somewhat, but he lost the stable eyepiece. His version is certainly less mobile than the simple Altitude-Azimuth scope. The astronomer can stand in one small area, but he still has to move around and look up and down and sideways, in often uncomfortable or painful angles.

After animating it, I can see the pros and cons, and it seems to me that the cons outweigh the pros. Hartness eliminated one of the two mirrors in the equatorial coudé, and expanded the range of available angles somewhat, but he lost the stable eyepiece. His version is certainly less mobile than the simple Altitude-Azimuth scope. The astronomer can stand in one small area, but he still has to move around and look up and down and sideways, in often uncomfortable or painful angles.

Hartness could have regained the perfectly still eyepiece while retaining the expanded range, by adding another mirror like this:

Hartness could have regained the perfectly still eyepiece while retaining the expanded range, by adding another mirror like this:

It's not clear why he didn't add this extra angle.

It's not clear why he didn't add this extra angle.