Tuesday, September 09, 2014

'Lone tree' theory doesn't work well

In the July superwindstorm I watched one set of trees thrashing, bending and finally breaking and squashing a house.

This is the nearest set of trees to the south of me. I had always watched this set in windstorms, because my own trees were too close to see. I figured this set would 'model' my own; if these started to get overly wild, I'd need to take cover.

After I got rid of my own wood weapons in 2011, I didn't feel the need to watch quite as often, but this storm transfixed me.

This is the nearest set of trees to the south of me. I had always watched this set in windstorms, because my own trees were too close to see. I figured this set would 'model' my own; if these started to get overly wild, I'd need to take cover.

After I got rid of my own wood weapons in 2011, I didn't feel the need to watch quite as often, but this storm transfixed me.

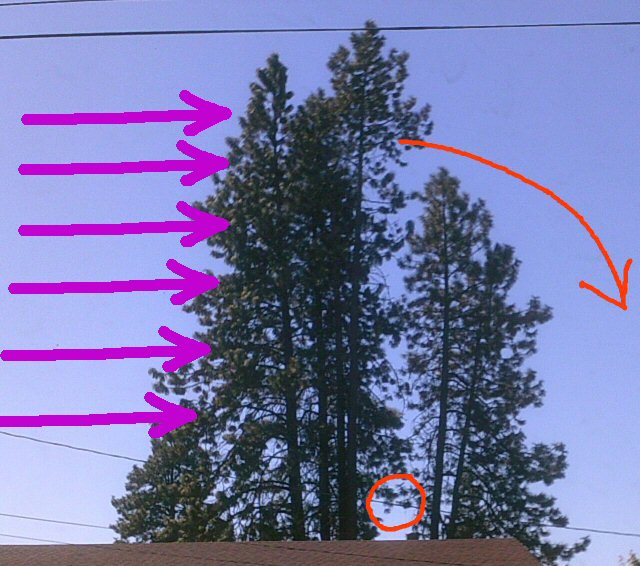

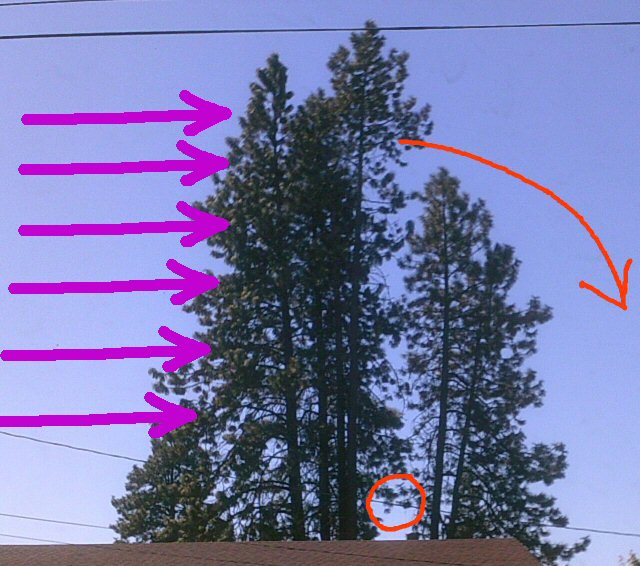

This set of trees is the nearest set to the north. In both pictures the circle indicates the breakpoint. It's behind a roof in the first pic, and just barely visible in the second one. [Graphics footnote: I can see the raw wood easily with naked eye, but my crappy camera won't cooperate. Also, I mirrored the first pic so the wind would come from the same side in both pics.]

The point of the pictures is to (at least partly) disprove the 'lone tree' theory.

It seems plausible that an unprotected tree, the first one to take the force of the wind, is more likely to fall than a protected or 'later' tree. I believed the lone tree notion until I took a close look at the house-squashes in this neighborhood. Out of 5 squashes, all were done by comparatively protected trees. The murder weapon was either in the middle of a group, or at the downwind end of a group. None of the killers were at the upwind end of a stand. The upwind trees didn't fall.

A better theory might start from the idea that back-pressure or physical backup matters more than pure applied wind pressure. The upwind tree in a group is buffeted on both sides by wind and branches. The ultimate or penultimate tree has less pressure on its leeward side. This is parallel to the basic principle of ventilation. Opening a window on the upwind side doesn't bring fresh air into your house unless there's an open window on the downwind side as well. When backpressure is absent, air moves.

This set of trees is the nearest set to the north. In both pictures the circle indicates the breakpoint. It's behind a roof in the first pic, and just barely visible in the second one. [Graphics footnote: I can see the raw wood easily with naked eye, but my crappy camera won't cooperate. Also, I mirrored the first pic so the wind would come from the same side in both pics.]

The point of the pictures is to (at least partly) disprove the 'lone tree' theory.

It seems plausible that an unprotected tree, the first one to take the force of the wind, is more likely to fall than a protected or 'later' tree. I believed the lone tree notion until I took a close look at the house-squashes in this neighborhood. Out of 5 squashes, all were done by comparatively protected trees. The murder weapon was either in the middle of a group, or at the downwind end of a group. None of the killers were at the upwind end of a stand. The upwind trees didn't fall.

A better theory might start from the idea that back-pressure or physical backup matters more than pure applied wind pressure. The upwind tree in a group is buffeted on both sides by wind and branches. The ultimate or penultimate tree has less pressure on its leeward side. This is parallel to the basic principle of ventilation. Opening a window on the upwind side doesn't bring fresh air into your house unless there's an open window on the downwind side as well. When backpressure is absent, air moves.

This is the nearest set of trees to the south of me. I had always watched this set in windstorms, because my own trees were too close to see. I figured this set would 'model' my own; if these started to get overly wild, I'd need to take cover.

After I got rid of my own wood weapons in 2011, I didn't feel the need to watch quite as often, but this storm transfixed me.

This is the nearest set of trees to the south of me. I had always watched this set in windstorms, because my own trees were too close to see. I figured this set would 'model' my own; if these started to get overly wild, I'd need to take cover.

After I got rid of my own wood weapons in 2011, I didn't feel the need to watch quite as often, but this storm transfixed me.

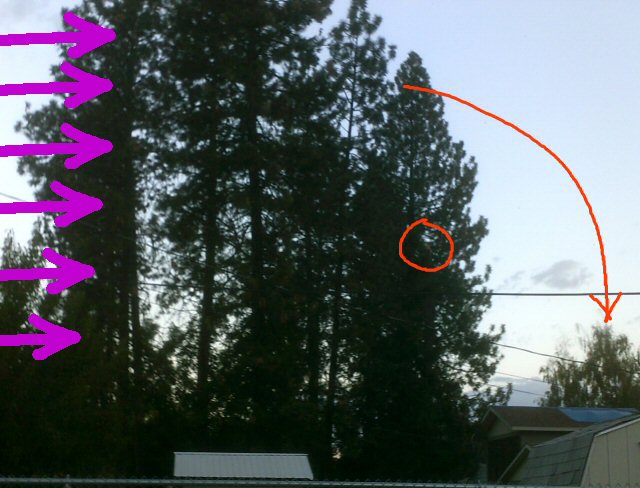

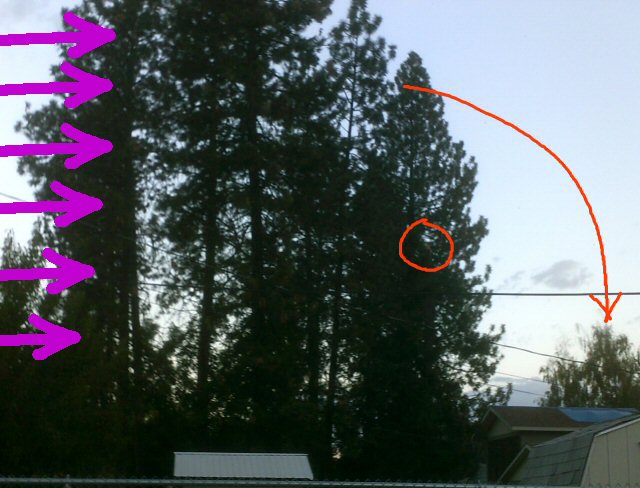

This set of trees is the nearest set to the north. In both pictures the circle indicates the breakpoint. It's behind a roof in the first pic, and just barely visible in the second one. [Graphics footnote: I can see the raw wood easily with naked eye, but my crappy camera won't cooperate. Also, I mirrored the first pic so the wind would come from the same side in both pics.]

The point of the pictures is to (at least partly) disprove the 'lone tree' theory.

It seems plausible that an unprotected tree, the first one to take the force of the wind, is more likely to fall than a protected or 'later' tree. I believed the lone tree notion until I took a close look at the house-squashes in this neighborhood. Out of 5 squashes, all were done by comparatively protected trees. The murder weapon was either in the middle of a group, or at the downwind end of a group. None of the killers were at the upwind end of a stand. The upwind trees didn't fall.

A better theory might start from the idea that back-pressure or physical backup matters more than pure applied wind pressure. The upwind tree in a group is buffeted on both sides by wind and branches. The ultimate or penultimate tree has less pressure on its leeward side. This is parallel to the basic principle of ventilation. Opening a window on the upwind side doesn't bring fresh air into your house unless there's an open window on the downwind side as well. When backpressure is absent, air moves.

This set of trees is the nearest set to the north. In both pictures the circle indicates the breakpoint. It's behind a roof in the first pic, and just barely visible in the second one. [Graphics footnote: I can see the raw wood easily with naked eye, but my crappy camera won't cooperate. Also, I mirrored the first pic so the wind would come from the same side in both pics.]

The point of the pictures is to (at least partly) disprove the 'lone tree' theory.

It seems plausible that an unprotected tree, the first one to take the force of the wind, is more likely to fall than a protected or 'later' tree. I believed the lone tree notion until I took a close look at the house-squashes in this neighborhood. Out of 5 squashes, all were done by comparatively protected trees. The murder weapon was either in the middle of a group, or at the downwind end of a group. None of the killers were at the upwind end of a stand. The upwind trees didn't fall.

A better theory might start from the idea that back-pressure or physical backup matters more than pure applied wind pressure. The upwind tree in a group is buffeted on both sides by wind and branches. The ultimate or penultimate tree has less pressure on its leeward side. This is parallel to the basic principle of ventilation. Opening a window on the upwind side doesn't bring fresh air into your house unless there's an open window on the downwind side as well. When backpressure is absent, air moves.Labels: Heimatkunde