Tuesday, September 17, 2019

Why haven't we returned to chordal writing?

We speak in chords, we hear in chords, we grammar in chords. Why don't we write or type in chords?

Expanded slightly:

Speech is chorded. The larynx is just a trigger for the complex and smooth modulation of harmonic patterns in vowels, shaped by the pharynx and tongue and lips.

Hearing is chorded. From the cochlea on up, the entire setup is harp-like, and the actual signals are parallel patterns of chords in parallel tone-based channels.

Grammar is chorded. English, the invading parasite, has lost some of the chordiness, but non-parasitic languages have complex and smooth patterns of harmony among morphemes on different words in the sentence, and harmony among vowels within and between words.

= = = = =

Some writing systems have their own internal harmony and continuo, but AFAIK no writing system tries to represent the harmony of speech or grammar.

So how come our language machines settled down into strictly monophonic and serial form? One keystroke adds one letter.

They didn't start that way.

Wheatstone's first telegraph had a chordal keyboard and a chordal readout. (Not surprising since Wheatstone came from a family that made accordions and concertinas!)

Other telegraphs were more piano-like.

Wheatstone's first telegraph had a chordal keyboard and a chordal readout. (Not surprising since Wheatstone came from a family that made accordions and concertinas!)

Other telegraphs were more piano-like.

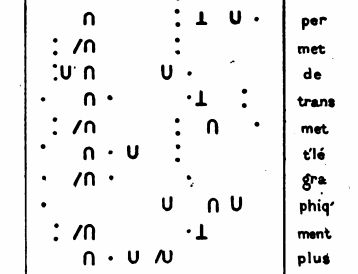

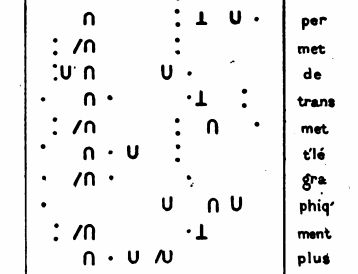

This is a steno-telegraph designed by Michela. You hit two or three keys with each hand, and the result was printed as a symbol for a syllable or word. Michela's written symbols were quasi-phonetic like Korean:

This is a steno-telegraph designed by Michela. You hit two or three keys with each hand, and the result was printed as a symbol for a syllable or word. Michela's written symbols were quasi-phonetic like Korean:

Chordal machines survive in courtroom transcription, but again they're not trying to represent the chordal aspects of sound or grammar. They simply type a group of letters simultaneously, and the stenographer later visually translates the peculiar letter combinations into words.

In the digital world it's possible to restore Michela's concept. A regular keyboard won't do because it's strictly one output at a time, but it should be possible to connect a pressure-sensitive MIDI keyboard to produce not only phonic chords but grammar chords.

Chordal machines survive in courtroom transcription, but again they're not trying to represent the chordal aspects of sound or grammar. They simply type a group of letters simultaneously, and the stenographer later visually translates the peculiar letter combinations into words.

In the digital world it's possible to restore Michela's concept. A regular keyboard won't do because it's strictly one output at a time, but it should be possible to connect a pressure-sensitive MIDI keyboard to produce not only phonic chords but grammar chords.

Wheatstone's first telegraph had a chordal keyboard and a chordal readout. (Not surprising since Wheatstone came from a family that made accordions and concertinas!)

Other telegraphs were more piano-like.

Wheatstone's first telegraph had a chordal keyboard and a chordal readout. (Not surprising since Wheatstone came from a family that made accordions and concertinas!)

Other telegraphs were more piano-like.

This is a steno-telegraph designed by Michela. You hit two or three keys with each hand, and the result was printed as a symbol for a syllable or word. Michela's written symbols were quasi-phonetic like Korean:

This is a steno-telegraph designed by Michela. You hit two or three keys with each hand, and the result was printed as a symbol for a syllable or word. Michela's written symbols were quasi-phonetic like Korean:

Chordal machines survive in courtroom transcription, but again they're not trying to represent the chordal aspects of sound or grammar. They simply type a group of letters simultaneously, and the stenographer later visually translates the peculiar letter combinations into words.

In the digital world it's possible to restore Michela's concept. A regular keyboard won't do because it's strictly one output at a time, but it should be possible to connect a pressure-sensitive MIDI keyboard to produce not only phonic chords but grammar chords.

Chordal machines survive in courtroom transcription, but again they're not trying to represent the chordal aspects of sound or grammar. They simply type a group of letters simultaneously, and the stenographer later visually translates the peculiar letter combinations into words.

In the digital world it's possible to restore Michela's concept. A regular keyboard won't do because it's strictly one output at a time, but it should be possible to connect a pressure-sensitive MIDI keyboard to produce not only phonic chords but grammar chords.Labels: defensible cases