Friday, June 15, 2018

Why it works

Here is an IMPORTANT piece of research.

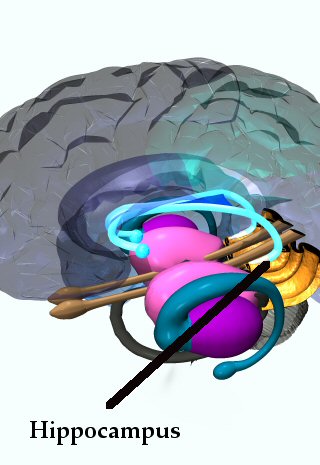

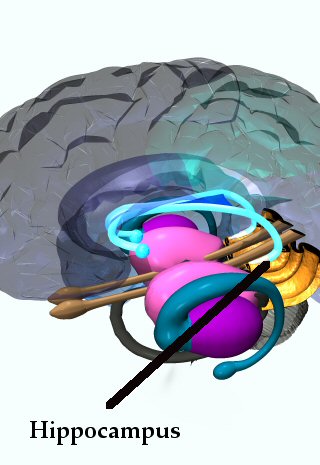

This picture is dominated by the light blue arch of the fornix, which crosslinks the hippocampus into other parts of the cortex.

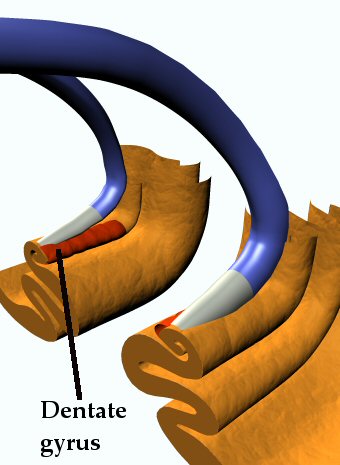

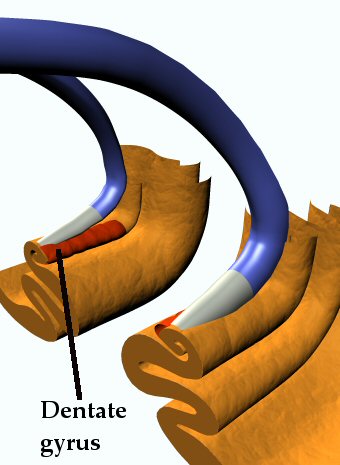

A closeup of the connection point where the fornix merges into the hippocampus shows that the dentate gyrus is a crucial 'modulator' for the connection.

This picture is dominated by the light blue arch of the fornix, which crosslinks the hippocampus into other parts of the cortex.

A closeup of the connection point where the fornix merges into the hippocampus shows that the dentate gyrus is a crucial 'modulator' for the connection.

So it's not surprising to find the dentate gyrus controlling associations, but the swamping or drowning-out effect is new and meaningful. It shows why one form of therapy works, and SHOULD cause "social" "scientists" to refine the effective therapy and abandon other forms of therapy. It won't, of course.

So it's not surprising to find the dentate gyrus controlling associations, but the swamping or drowning-out effect is new and meaningful. It shows why one form of therapy works, and SHOULD cause "social" "scientists" to refine the effective therapy and abandon other forms of therapy. It won't, of course.

In the field of treating traumatic memories there has been a long-debated question of whether fear attenuation involves the suppression of the original memory trace of fear by a new memory trace of safety or the rewriting of the original fear trace towards safety. Part of the debate has to do with the fact that we still don't understand exactly how neurons store memories in general. Although they don't exclude suppression, the findings from this study show for the first time the importance of rewriting in treating traumatic memories. Using a fear-training exercise that produces long-lasting traumatic memories, the scientists first identified the subpopulation of neurons in the dentate gyrus that are involved in storing long-term traumatic memories. The mice then underwent fear-reducing training, which resembles exposure-based therapy in humans -- the most efficient form of trauma therapy in humans today. Surprisingly, when the researchers looked again into the brain of the mice, some of the neurons active at recalling the traumatic memories were still active when the animals no longer showed fear. Importantly, the less the mice were scared, the more cells became reactivated.In other words, re-conditioning a memory away from panic doesn't mean getting rid of the memory. It means drowning out the panic waves with new comfort waves, which must be more intense than the original panic waves. The conditioning specifically affects one area in the dentate gyrus:

Finally, when the researchers enhanced the excitability of these recall neurons during the therapeutic intervention, they found that the mice showed improved fear reduction. Thus, they concluded that attenuating remote fear memories depends on the continued activity of the neurons they identified in the dentate gyrus.= = = = = The hippocampus is the 'hemstitch' at the bottom edge of the temporal lobe, seen here:

This picture is dominated by the light blue arch of the fornix, which crosslinks the hippocampus into other parts of the cortex.

A closeup of the connection point where the fornix merges into the hippocampus shows that the dentate gyrus is a crucial 'modulator' for the connection.

This picture is dominated by the light blue arch of the fornix, which crosslinks the hippocampus into other parts of the cortex.

A closeup of the connection point where the fornix merges into the hippocampus shows that the dentate gyrus is a crucial 'modulator' for the connection.

So it's not surprising to find the dentate gyrus controlling associations, but the swamping or drowning-out effect is new and meaningful. It shows why one form of therapy works, and SHOULD cause "social" "scientists" to refine the effective therapy and abandon other forms of therapy. It won't, of course.

So it's not surprising to find the dentate gyrus controlling associations, but the swamping or drowning-out effect is new and meaningful. It shows why one form of therapy works, and SHOULD cause "social" "scientists" to refine the effective therapy and abandon other forms of therapy. It won't, of course.