Sunday, January 22, 2017

1933 MIDI

Programmable mechanisms for entertainment go back a LONG way. Greeks were making water-driven clocks and animals 2000 years ago. Around 1200AD the trend started again with clockwork. Music boxes expanded into orchestras with human-like performers.

Analog electronics didn't join the trend in a major way. Some fountains and carillons were driven by music-box technology through relays instead of gears, but that's not really electronic.

Here's one attempt at a fully electronic music box, found in a 1933 radio journal.

The Talk-A-Lite by Operadio. Clearly not a home consumer product. Chassis to be mounted in some larger setup. Seems to have several switches on the front, Strowger relays inside and a turntable on top. But how does it work?

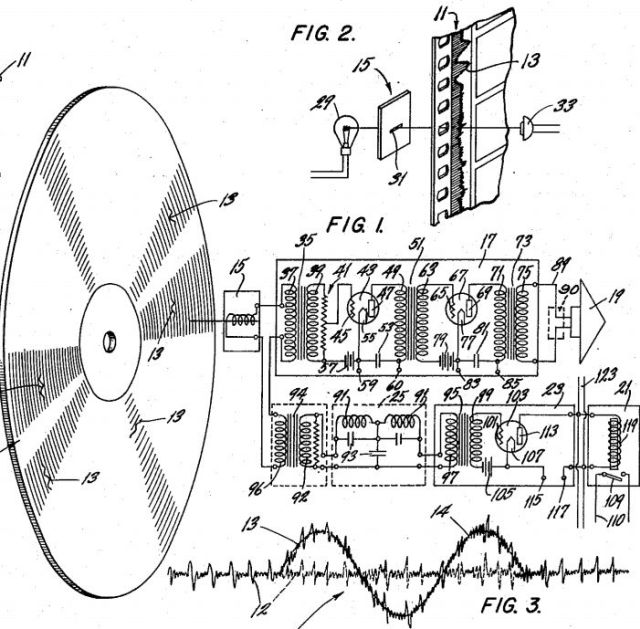

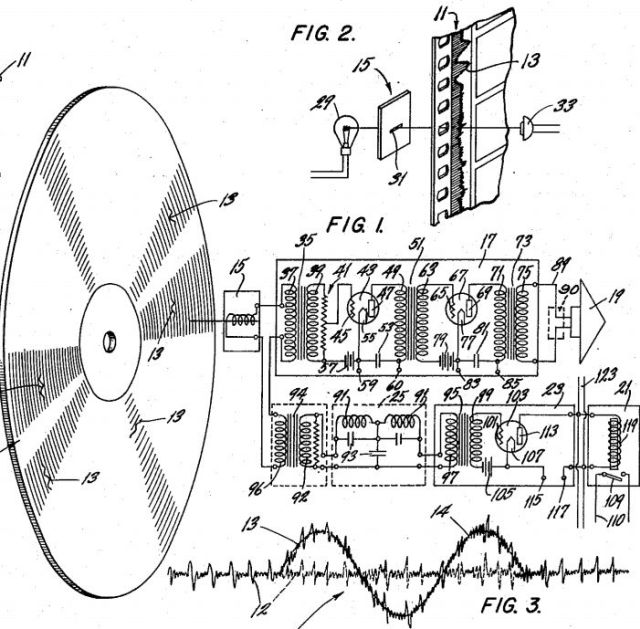

Fortunately the patent was available, and clearly shows the mechanism.

The Talk-A-Lite by Operadio. Clearly not a home consumer product. Chassis to be mounted in some larger setup. Seems to have several switches on the front, Strowger relays inside and a turntable on top. But how does it work?

Fortunately the patent was available, and clearly shows the mechanism.

On the top part of the circuit you can see the turntable, the needle (15), leading to a simple amplifier with speaker (19). This part is just a phonograph.

= = = = =

The system takes advantage of a basic property of hearing. If two signals are ADDED or mixed linearly, we hear them separately. The control signals (big wiggles on the wave) are ADDED to the speech or music (small sharp wiggles). Because the control waves are too slow for us to hear, we don't even notice them. [You'd also want the upper amplifier to be AC-coupled so the speaker doesn't move with the control wiggles. This was default design for tube amps, so the inventor probably didn't think it was worth specifying.]

To demonstrate, I pulled a few seconds from a Ripley radio program that sounds sort of educational, then generated a couple of control pulses typical of the patent's concept.

Separate waves as seen in Audacity:

On the top part of the circuit you can see the turntable, the needle (15), leading to a simple amplifier with speaker (19). This part is just a phonograph.

= = = = =

The system takes advantage of a basic property of hearing. If two signals are ADDED or mixed linearly, we hear them separately. The control signals (big wiggles on the wave) are ADDED to the speech or music (small sharp wiggles). Because the control waves are too slow for us to hear, we don't even notice them. [You'd also want the upper amplifier to be AC-coupled so the speaker doesn't move with the control wiggles. This was default design for tube amps, so the inventor probably didn't think it was worth specifying.]

To demonstrate, I pulled a few seconds from a Ripley radio program that sounds sort of educational, then generated a couple of control pulses typical of the patent's concept.

Separate waves as seen in Audacity:

Hear the Ripley by itself.

Hear the control pulse by itself.

After adding the two waves, you can see the mixing clearly in the waveform.

Hear the Ripley by itself.

Hear the control pulse by itself.

After adding the two waves, you can see the mixing clearly in the waveform.

Can you hear it?

Hear the mixture.

Despite the appearance, you can't hear the control pulses.

= = = = =

The lower part of the circuit leads to the real action, which is described in the text but not shown completely as a schematic. Several tunable circuits pick up the various control tones, and each tuned circuit kicks a Strowger relay forward by one step when it picks up its own tone. You would then tie your lights or solenoids to appropriate outputs of the Strowgers.

Can you hear it?

Hear the mixture.

Despite the appearance, you can't hear the control pulses.

= = = = =

The lower part of the circuit leads to the real action, which is described in the text but not shown completely as a schematic. Several tunable circuits pick up the various control tones, and each tuned circuit kicks a Strowger relay forward by one step when it picks up its own tone. You would then tie your lights or solenoids to appropriate outputs of the Strowgers.

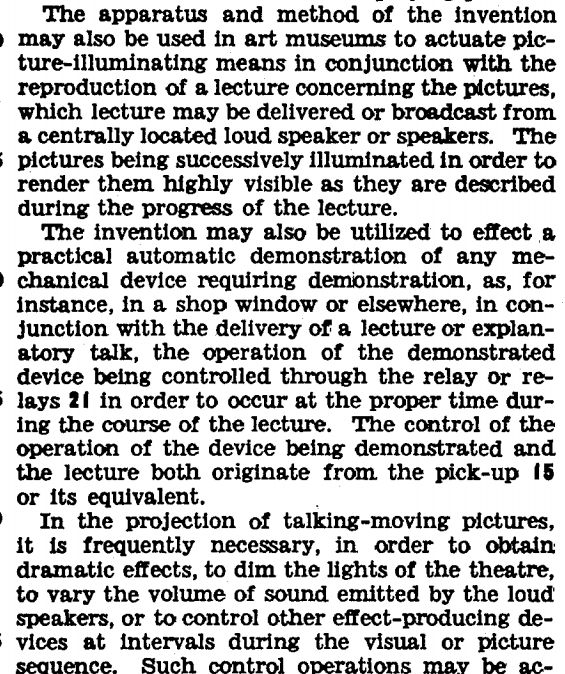

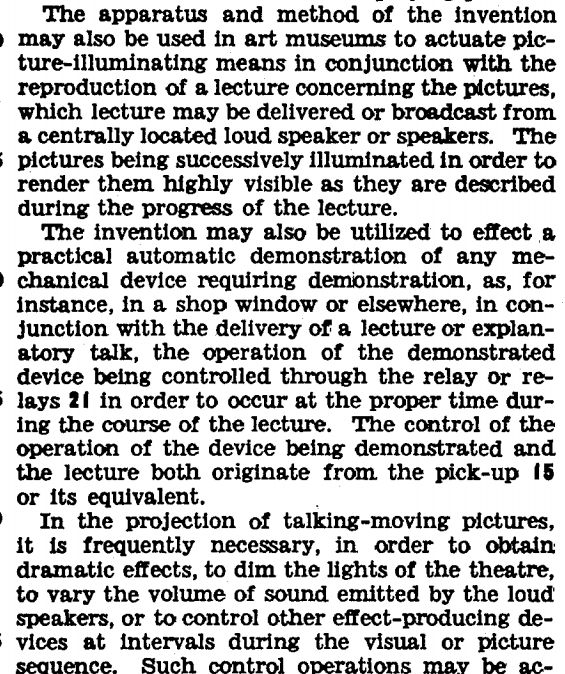

The inventors did a good job of imagining a wide range of uses. You could click through a sequence of pictures, or demonstrate some phenomenon or device, or trigger special effects in a theater.

I don't see any reason why it wouldn't work, and it was obviously manufactured and sold. But it didn't succeed, and we didn't get true electronic control until the digital era when MIDI came along.

= = = = =

Sidenote: The Wiki article on Strowger mentions something I hadn't heard before: Alton Strowger sold out of Automatic Electric a few years after he founded it. He decided to take a flat payment of $10k (roughly $200k today) instead of royalties on the patent. Dumb.

The Ripley show mentions that Columbus decided to take a flat annual payment of $16k instead of a 10% royalty on all the gold and resources flowing from America to Spain. Dumb. [Episode not online AFAIK, so here's a longer segment to show what I mean.]

But: as usual, reality wasn't as simple as Ripley. Columbus himself accepted the 10% royalty, then he got crossgrained with the Spanish government, at one point allying himself with some of the Injun tribes (!!!!!!!) against the king. When he returned to Spain he was jailed for a while. Even so, the 10% deal was still in place when Chris died in 1506. His heirs got even more crossgrained, continuously suing for more power and money. The suits were finally arbitrated in 1536, giving the heirs some meaningless titles and 16k ducats per year. This website says a 1500s ducat was about $25 in modern money, so 16k ducats would have been about 20k dollars in the 1930s or 400k dollars today. Ripley was right on the amount, wrong on the sequence of events, wrong on the claim of injustice. Chris got a good deal and accepted it. His heirs got what they deserved for being litigious dickheads.

Moral of the story: Unless you're 100% certain that the company or the contract is going to fail within a year, TAKE THE ROYALTIES. And the unless doesn't even matter. If the company is already failing it won't be able to pay the flat sum anyway. So the rule reduces to TAKE THE ROYALTIES.

The inventors did a good job of imagining a wide range of uses. You could click through a sequence of pictures, or demonstrate some phenomenon or device, or trigger special effects in a theater.

I don't see any reason why it wouldn't work, and it was obviously manufactured and sold. But it didn't succeed, and we didn't get true electronic control until the digital era when MIDI came along.

= = = = =

Sidenote: The Wiki article on Strowger mentions something I hadn't heard before: Alton Strowger sold out of Automatic Electric a few years after he founded it. He decided to take a flat payment of $10k (roughly $200k today) instead of royalties on the patent. Dumb.

The Ripley show mentions that Columbus decided to take a flat annual payment of $16k instead of a 10% royalty on all the gold and resources flowing from America to Spain. Dumb. [Episode not online AFAIK, so here's a longer segment to show what I mean.]

But: as usual, reality wasn't as simple as Ripley. Columbus himself accepted the 10% royalty, then he got crossgrained with the Spanish government, at one point allying himself with some of the Injun tribes (!!!!!!!) against the king. When he returned to Spain he was jailed for a while. Even so, the 10% deal was still in place when Chris died in 1506. His heirs got even more crossgrained, continuously suing for more power and money. The suits were finally arbitrated in 1536, giving the heirs some meaningless titles and 16k ducats per year. This website says a 1500s ducat was about $25 in modern money, so 16k ducats would have been about 20k dollars in the 1930s or 400k dollars today. Ripley was right on the amount, wrong on the sequence of events, wrong on the claim of injustice. Chris got a good deal and accepted it. His heirs got what they deserved for being litigious dickheads.

Moral of the story: Unless you're 100% certain that the company or the contract is going to fail within a year, TAKE THE ROYALTIES. And the unless doesn't even matter. If the company is already failing it won't be able to pay the flat sum anyway. So the rule reduces to TAKE THE ROYALTIES.

The Talk-A-Lite by Operadio. Clearly not a home consumer product. Chassis to be mounted in some larger setup. Seems to have several switches on the front, Strowger relays inside and a turntable on top. But how does it work?

Fortunately the patent was available, and clearly shows the mechanism.

The Talk-A-Lite by Operadio. Clearly not a home consumer product. Chassis to be mounted in some larger setup. Seems to have several switches on the front, Strowger relays inside and a turntable on top. But how does it work?

Fortunately the patent was available, and clearly shows the mechanism.

On the top part of the circuit you can see the turntable, the needle (15), leading to a simple amplifier with speaker (19). This part is just a phonograph.

= = = = =

The system takes advantage of a basic property of hearing. If two signals are ADDED or mixed linearly, we hear them separately. The control signals (big wiggles on the wave) are ADDED to the speech or music (small sharp wiggles). Because the control waves are too slow for us to hear, we don't even notice them. [You'd also want the upper amplifier to be AC-coupled so the speaker doesn't move with the control wiggles. This was default design for tube amps, so the inventor probably didn't think it was worth specifying.]

To demonstrate, I pulled a few seconds from a Ripley radio program that sounds sort of educational, then generated a couple of control pulses typical of the patent's concept.

Separate waves as seen in Audacity:

On the top part of the circuit you can see the turntable, the needle (15), leading to a simple amplifier with speaker (19). This part is just a phonograph.

= = = = =

The system takes advantage of a basic property of hearing. If two signals are ADDED or mixed linearly, we hear them separately. The control signals (big wiggles on the wave) are ADDED to the speech or music (small sharp wiggles). Because the control waves are too slow for us to hear, we don't even notice them. [You'd also want the upper amplifier to be AC-coupled so the speaker doesn't move with the control wiggles. This was default design for tube amps, so the inventor probably didn't think it was worth specifying.]

To demonstrate, I pulled a few seconds from a Ripley radio program that sounds sort of educational, then generated a couple of control pulses typical of the patent's concept.

Separate waves as seen in Audacity:

Hear the Ripley by itself.

Hear the control pulse by itself.

After adding the two waves, you can see the mixing clearly in the waveform.

Hear the Ripley by itself.

Hear the control pulse by itself.

After adding the two waves, you can see the mixing clearly in the waveform.

Can you hear it?

Hear the mixture.

Despite the appearance, you can't hear the control pulses.

= = = = =

The lower part of the circuit leads to the real action, which is described in the text but not shown completely as a schematic. Several tunable circuits pick up the various control tones, and each tuned circuit kicks a Strowger relay forward by one step when it picks up its own tone. You would then tie your lights or solenoids to appropriate outputs of the Strowgers.

Can you hear it?

Hear the mixture.

Despite the appearance, you can't hear the control pulses.

= = = = =

The lower part of the circuit leads to the real action, which is described in the text but not shown completely as a schematic. Several tunable circuits pick up the various control tones, and each tuned circuit kicks a Strowger relay forward by one step when it picks up its own tone. You would then tie your lights or solenoids to appropriate outputs of the Strowgers.

The inventors did a good job of imagining a wide range of uses. You could click through a sequence of pictures, or demonstrate some phenomenon or device, or trigger special effects in a theater.

I don't see any reason why it wouldn't work, and it was obviously manufactured and sold. But it didn't succeed, and we didn't get true electronic control until the digital era when MIDI came along.

= = = = =

Sidenote: The Wiki article on Strowger mentions something I hadn't heard before: Alton Strowger sold out of Automatic Electric a few years after he founded it. He decided to take a flat payment of $10k (roughly $200k today) instead of royalties on the patent. Dumb.

The Ripley show mentions that Columbus decided to take a flat annual payment of $16k instead of a 10% royalty on all the gold and resources flowing from America to Spain. Dumb. [Episode not online AFAIK, so here's a longer segment to show what I mean.]

But: as usual, reality wasn't as simple as Ripley. Columbus himself accepted the 10% royalty, then he got crossgrained with the Spanish government, at one point allying himself with some of the Injun tribes (!!!!!!!) against the king. When he returned to Spain he was jailed for a while. Even so, the 10% deal was still in place when Chris died in 1506. His heirs got even more crossgrained, continuously suing for more power and money. The suits were finally arbitrated in 1536, giving the heirs some meaningless titles and 16k ducats per year. This website says a 1500s ducat was about $25 in modern money, so 16k ducats would have been about 20k dollars in the 1930s or 400k dollars today. Ripley was right on the amount, wrong on the sequence of events, wrong on the claim of injustice. Chris got a good deal and accepted it. His heirs got what they deserved for being litigious dickheads.

Moral of the story: Unless you're 100% certain that the company or the contract is going to fail within a year, TAKE THE ROYALTIES. And the unless doesn't even matter. If the company is already failing it won't be able to pay the flat sum anyway. So the rule reduces to TAKE THE ROYALTIES.

The inventors did a good job of imagining a wide range of uses. You could click through a sequence of pictures, or demonstrate some phenomenon or device, or trigger special effects in a theater.

I don't see any reason why it wouldn't work, and it was obviously manufactured and sold. But it didn't succeed, and we didn't get true electronic control until the digital era when MIDI came along.

= = = = =

Sidenote: The Wiki article on Strowger mentions something I hadn't heard before: Alton Strowger sold out of Automatic Electric a few years after he founded it. He decided to take a flat payment of $10k (roughly $200k today) instead of royalties on the patent. Dumb.

The Ripley show mentions that Columbus decided to take a flat annual payment of $16k instead of a 10% royalty on all the gold and resources flowing from America to Spain. Dumb. [Episode not online AFAIK, so here's a longer segment to show what I mean.]

But: as usual, reality wasn't as simple as Ripley. Columbus himself accepted the 10% royalty, then he got crossgrained with the Spanish government, at one point allying himself with some of the Injun tribes (!!!!!!!) against the king. When he returned to Spain he was jailed for a while. Even so, the 10% deal was still in place when Chris died in 1506. His heirs got even more crossgrained, continuously suing for more power and money. The suits were finally arbitrated in 1536, giving the heirs some meaningless titles and 16k ducats per year. This website says a 1500s ducat was about $25 in modern money, so 16k ducats would have been about 20k dollars in the 1930s or 400k dollars today. Ripley was right on the amount, wrong on the sequence of events, wrong on the claim of injustice. Chris got a good deal and accepted it. His heirs got what they deserved for being litigious dickheads.

Moral of the story: Unless you're 100% certain that the company or the contract is going to fail within a year, TAKE THE ROYALTIES. And the unless doesn't even matter. If the company is already failing it won't be able to pay the flat sum anyway. So the rule reduces to TAKE THE ROYALTIES.