Sunday, May 08, 2016

The Eful tower

When reading old documents about mineral waters I noticed an odd spelling convention. Chemical names ending in ite, ide and ine were eless. Chlorid, bromin, dioxid, Thermit. (Thermit was a brand-ish name for an explosive.)

I ass-u-me-d that the eless version had been constant until sometime in the 20th century, when some sort of academic agreement put the e's in.

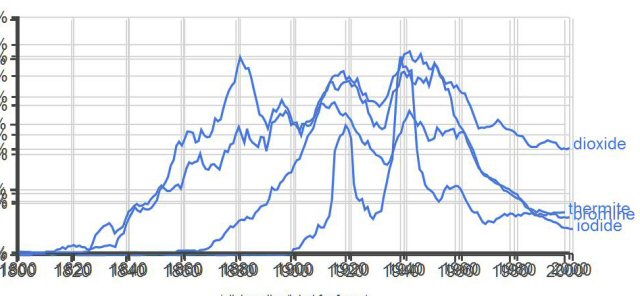

Google's ngram pins it down, with an obvious explanation for the return of e's, but a non-obvious picture at the other end.

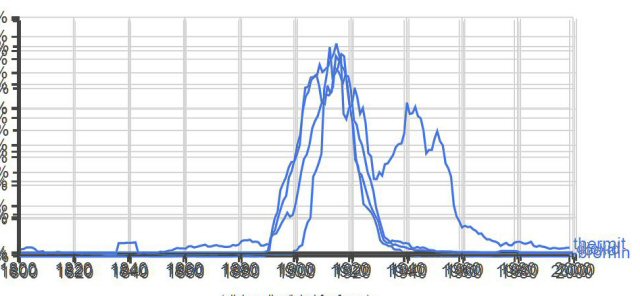

Here are the eless versions:

(Thermit lasted longer, presumably because it was a trademark.)

No doubt about the endpoint. The eless versions were Kraut spellings. American academia was madly in love with all things German, including the spellings of chemicals. WW1 ended the love affair. The end was visible in all sorts of publications. In 1917 streetcar companies and electronic experimenters and carmakers were looking to Berlin for advice. In 1918 they were ready to obliterate Berlin, even though Berlin hadn't actually bothered or bombed us.

But what about the startpoint?

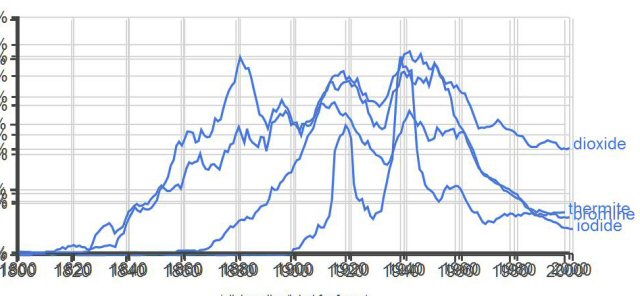

This ngram shows that the eful versions, the more natural forms, were dominant BEFORE the eless Kraut versions and remained dominant all the way through. They weren't replaced by the eless.

(Thermit lasted longer, presumably because it was a trademark.)

No doubt about the endpoint. The eless versions were Kraut spellings. American academia was madly in love with all things German, including the spellings of chemicals. WW1 ended the love affair. The end was visible in all sorts of publications. In 1917 streetcar companies and electronic experimenters and carmakers were looking to Berlin for advice. In 1918 they were ready to obliterate Berlin, even though Berlin hadn't actually bothered or bombed us.

But what about the startpoint?

This ngram shows that the eful versions, the more natural forms, were dominant BEFORE the eless Kraut versions and remained dominant all the way through. They weren't replaced by the eless.

English normally follows French when it brings in Latin or Greek, so Latin itus or itum becomes ite. Why did part of academia switch to German forms around 1890? Germany united for the first time in 1870 and became powerful thereafter, but 1870 wasn't a major event for Americans overall. Not an obvious explanation.

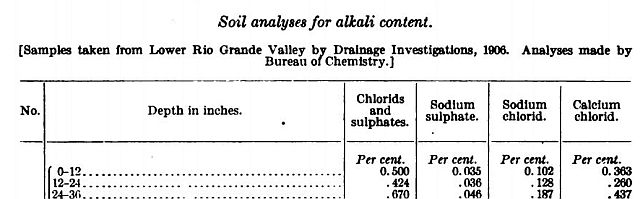

Oddly, the Kraut de-e-ification did NOT affect -ate compounds.

English normally follows French when it brings in Latin or Greek, so Latin itus or itum becomes ite. Why did part of academia switch to German forms around 1890? Germany united for the first time in 1870 and became powerful thereafter, but 1870 wasn't a major event for Americans overall. Not an obvious explanation.

Oddly, the Kraut de-e-ification did NOT affect -ate compounds.

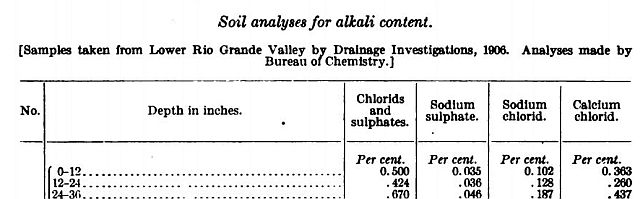

Chlorids and sulphates in this 1906 USDA publication.

Chlorids and sulphates in this 1906 USDA publication.

(Thermit lasted longer, presumably because it was a trademark.)

No doubt about the endpoint. The eless versions were Kraut spellings. American academia was madly in love with all things German, including the spellings of chemicals. WW1 ended the love affair. The end was visible in all sorts of publications. In 1917 streetcar companies and electronic experimenters and carmakers were looking to Berlin for advice. In 1918 they were ready to obliterate Berlin, even though Berlin hadn't actually bothered or bombed us.

But what about the startpoint?

This ngram shows that the eful versions, the more natural forms, were dominant BEFORE the eless Kraut versions and remained dominant all the way through. They weren't replaced by the eless.

(Thermit lasted longer, presumably because it was a trademark.)

No doubt about the endpoint. The eless versions were Kraut spellings. American academia was madly in love with all things German, including the spellings of chemicals. WW1 ended the love affair. The end was visible in all sorts of publications. In 1917 streetcar companies and electronic experimenters and carmakers were looking to Berlin for advice. In 1918 they were ready to obliterate Berlin, even though Berlin hadn't actually bothered or bombed us.

But what about the startpoint?

This ngram shows that the eful versions, the more natural forms, were dominant BEFORE the eless Kraut versions and remained dominant all the way through. They weren't replaced by the eless.

English normally follows French when it brings in Latin or Greek, so Latin itus or itum becomes ite. Why did part of academia switch to German forms around 1890? Germany united for the first time in 1870 and became powerful thereafter, but 1870 wasn't a major event for Americans overall. Not an obvious explanation.

Oddly, the Kraut de-e-ification did NOT affect -ate compounds.

English normally follows French when it brings in Latin or Greek, so Latin itus or itum becomes ite. Why did part of academia switch to German forms around 1890? Germany united for the first time in 1870 and became powerful thereafter, but 1870 wasn't a major event for Americans overall. Not an obvious explanation.

Oddly, the Kraut de-e-ification did NOT affect -ate compounds.

Chlorids and sulphates in this 1906 USDA publication.

Chlorids and sulphates in this 1906 USDA publication.Labels: Asked and answered